ASEAN replaced the European Union as China’s biggest trading partner in 1Q20. A major contributor to that was the United Kingdom dropping out of EU statistics following Brexit. This also reflects the growing integration of ASEAN into so-called “China Plus One” supply chains.

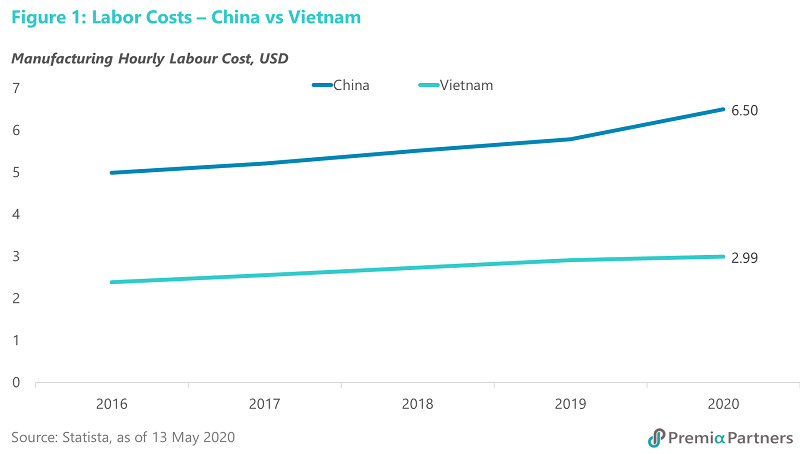

ASEAN and China – part of an expanded regional supply chain rather than mutually exclusive solutions. China’s rising labour cost has been a concern for years. According to Statista, the average manufacturing labour cost in China has risen from USD 4.99 per hour in 2016 to USD 6.50 currently. This compares to USD 2.99 for Vietnam this year (Figure 1). Then there are higher land costs.

The last two years saw additional concerns over US protectionist measures targeting China.

Most recently, there was the expectation, as a result of COVID-19, that major international corporations would rapidly shift their supply chains out of China to protect themselves from production disruptions in China.

Yet, a more nuanced picture is closer to the truth, i.e., the shifts in supply chains are more likely to be gradual than dramatic.

The speed and effectiveness of China’s COVID-19 response will likely cause a rethink of the idea of production retreat from China.

Companies, which will suffer from considerable damage to their cashflow and even balance sheets as a result of COVID-19, are unlikely to spend more on investments in alternative supply chains. In any event, companies will amortise their existing facilities before they move to new locations. Even in an extreme “uprooting” scenario, that will by financial necessity be gradual.

Beyond wage and land costs, there is another consideration of a critical mass of component suppliers in close proximity.

ASEAN is big enough to supplement but not big enough to replace the China supply chain.

Access to the Chinese consumer market is another major consideration.

Given the different relative sizes of the two economies, the supply chain shifts will have assymetric impacts on China Vs ASEAN – having greater beneficial effects for ASEAN economies than negative effects on China.

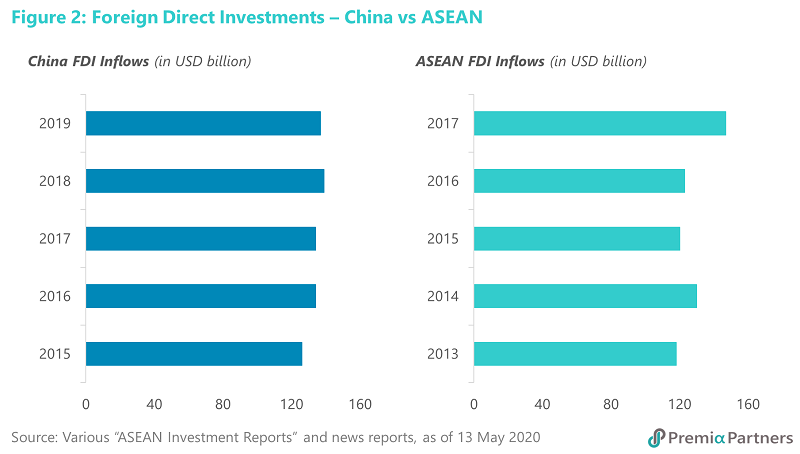

Despite the trade tensions in 2018-2019, China recorded 5.8% growth in foreign direct investments (in local currency terms) in 2019 to CNY 941.5 billion (US$137 billion). Despite years of talk about shifting supply chains away from China, FDI inflows have been very stable. ASEAN’s gains cannot be identified as China’s loss, especially in CNY terms (Figures 2).

China Plus One will gather more momentum if regional trade blocs develop.

The China Plus One supply chain strategy is about international companies adding new production facilities in other developing Asian countries to supplement existing operations in China.

Instead of major shifts of supply chains away from China, what is more likely to occur over coming years are small scale, gradual and industry-specific shifts.

As the US targets “Made in China” for trade barriers, it is logical for even Chinese manufacturers to relocate final production out of China while sourcing inputs from China. Even without the trade war driver, such relocations are recommended anyway by classic “comparative advantage” strategies. The trade tensions with the US would have just accelerated production shifts which would make China more economically efficient.

Further, ASEAN makes the most sense as a new supply chain can be developed close to China, minimising logistic costs. In the process, ASEAN is enmeshed even more in a Chinese economic, if not trade, bloc.

Vietnam, given its shared border with China, has been a major winner from the investment spillovers from “China Plus One”.

Vietnam: Continuing Outperformance

Vietnam’s Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc last week said his country was aiming for above-5% GDP growth this year.

It’s ambitious. But then again, Vietnam turned in 3.8% growth y/y for 1Q20, amidst an aggressive lockdown. That is a pretty remarkable growth outcome given the big GDP declines recorded almost everywhere else in the world.

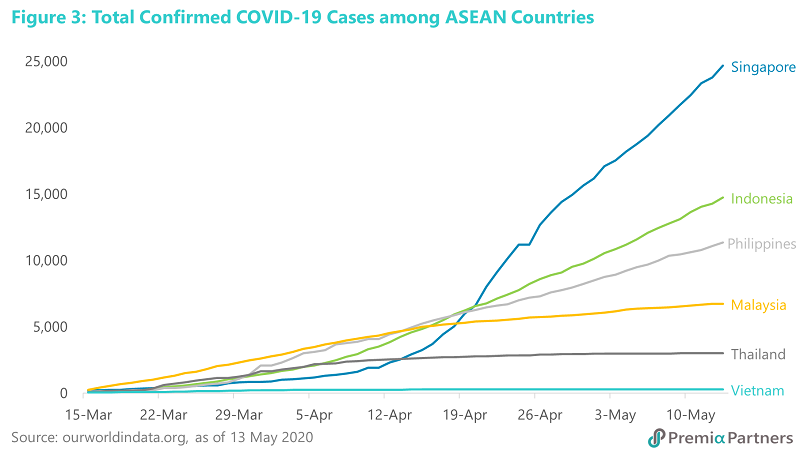

Vietnam’s management of COVID-19 has been well documented in the media, with its data has been judged by numerous independent experts as credible.

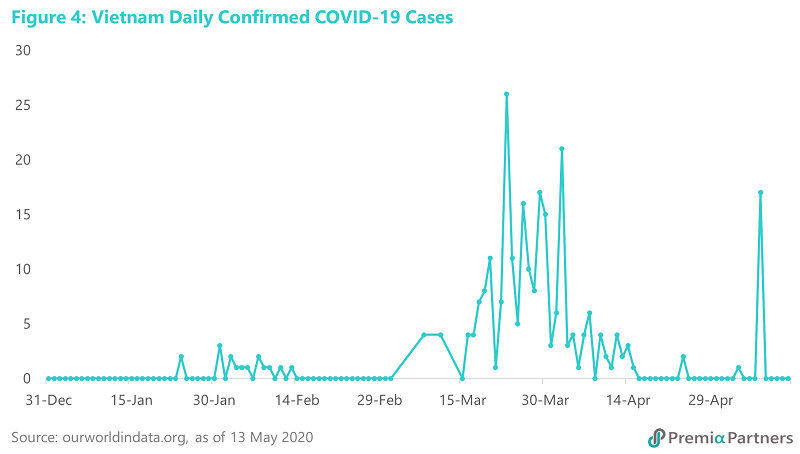

The key factors behind its success have been: tough and early government action, targeted lockdowns, social discipline/control, temperature screening and virus testing. For a developing country, it is remarkable that Vietnam has not had one death attributable to COVID-19.

Vietnam ended social isolation on 23 April. Nonetheless, continued restrictions on mass gatherings and the mandatory wearing of masks remain in place. Three weeks later, the number of new cases has been generally very low relative to almost anywhere else in the world (Figures 3, 4).

An interesting side story is how Vietnam went from being an importer COVID-19 testing kits from Korea and Germany to a mass producer of “Made-In-Vietnam” kits, in around two months. Late last month, the World Health Organisation approved a Made-In-Vietnam COVID-19 test kit. They are now in mass production for export.

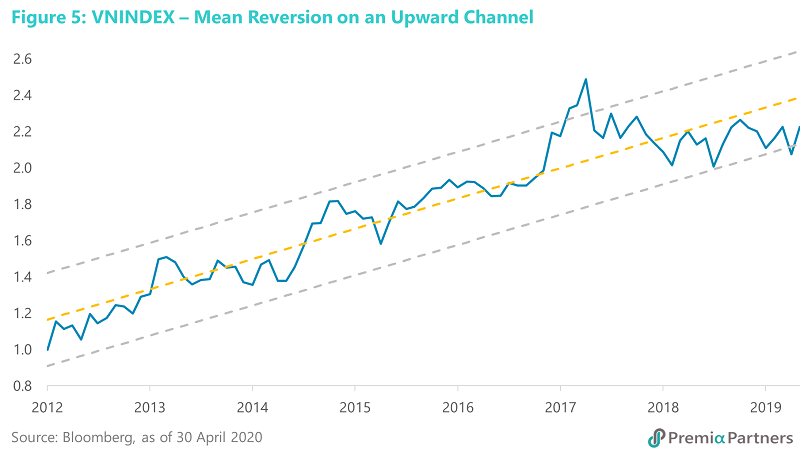

All this goes some way to explaining how through the COVID-19 pandemic to date, the Vietnam Ho Chih Minh Index (VNINDEX) has continued on its path of outperformance against the FTSE ASEAN 40 index (FA40) (Figure 5). Indeed, over ther past eight years, VNINDEX/FA40 has been a relative outperformance story of mean reversion on a rising trendline.

Related reading:

Postcard from Vietnam: Updates on market, macro and various with reopening underway

Will China’s GDP overtake the US this decade?