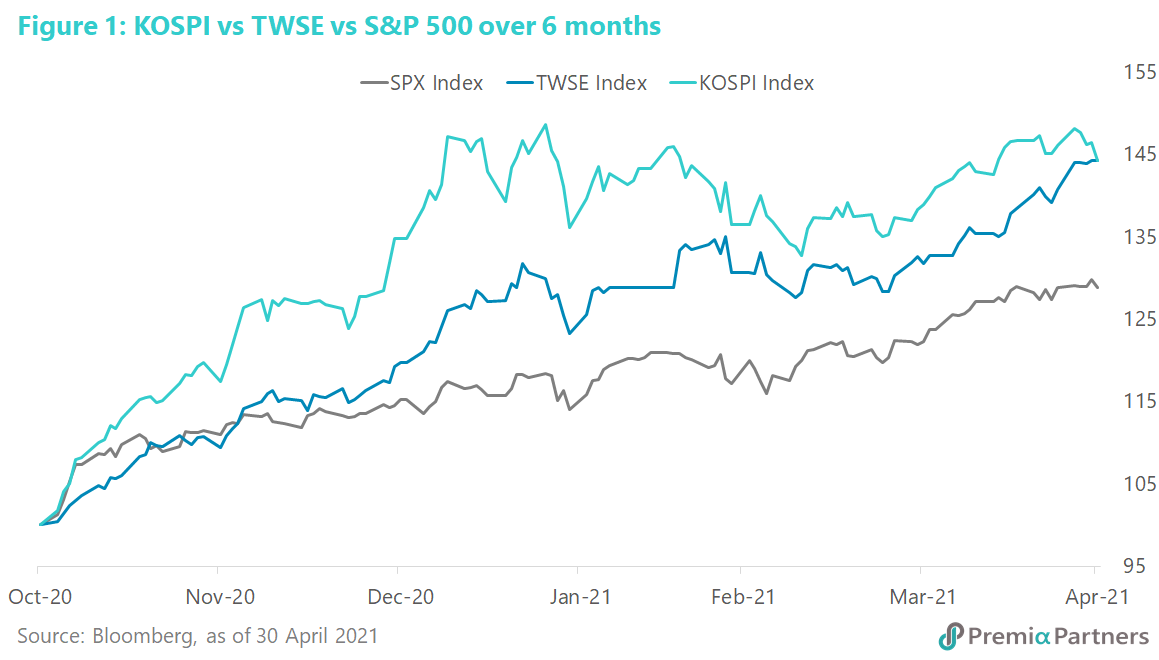

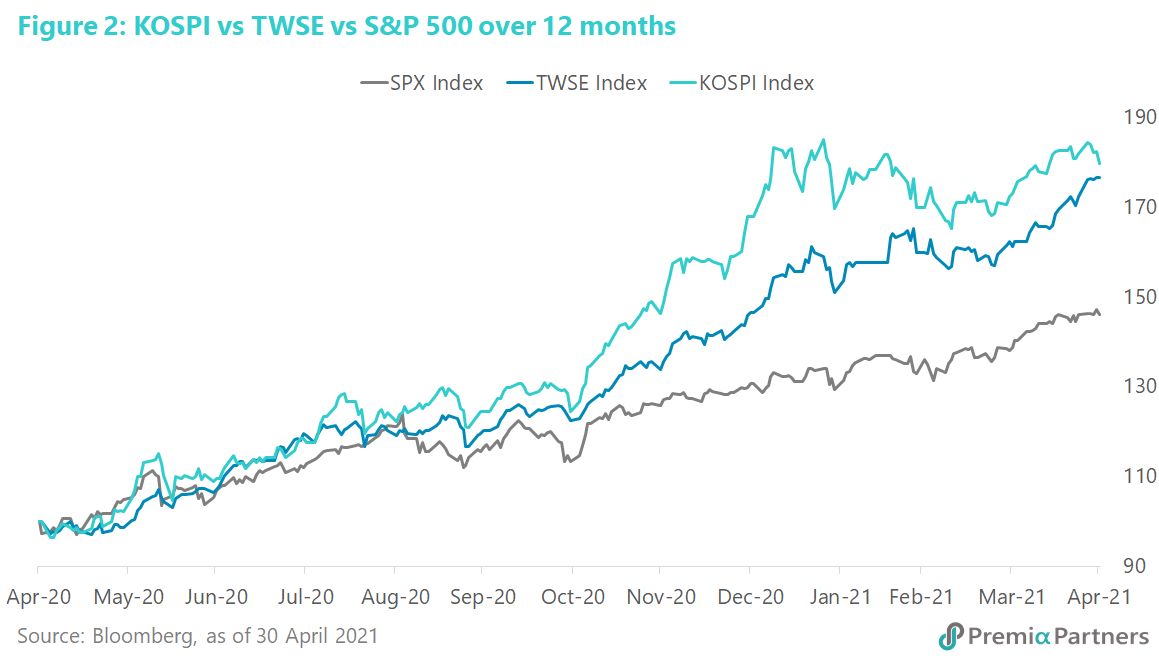

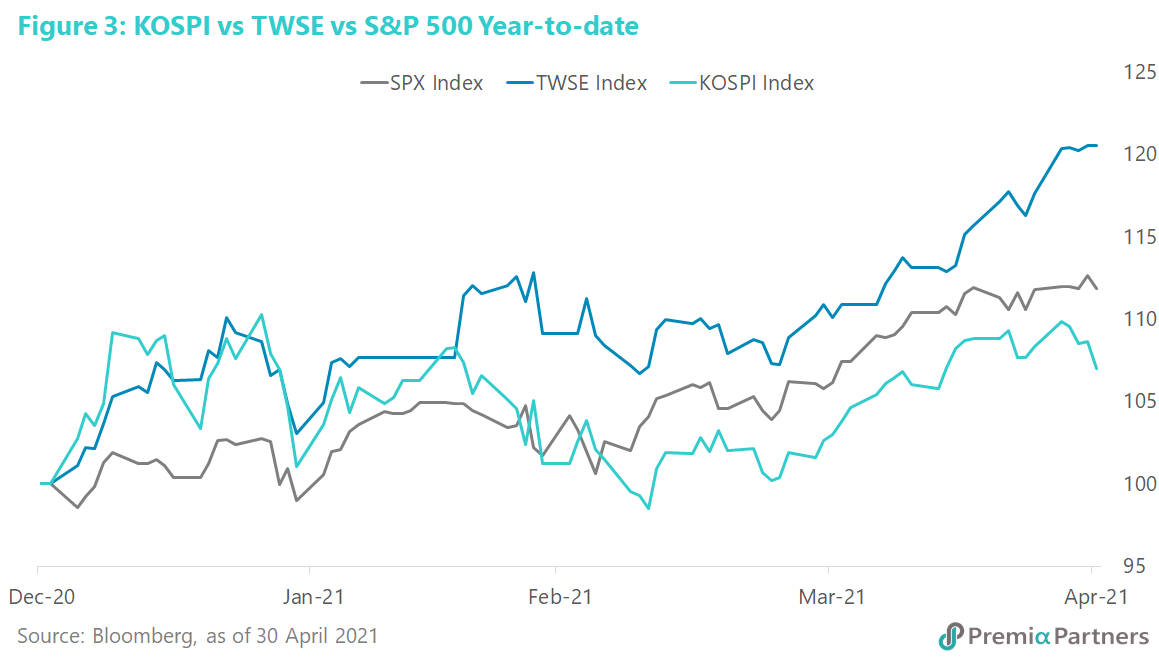

KOSPI and TWSE outperformed the S&P 500 over 6 months and 12 months. South Korea’s KOSPI and Taiwan’s TWSE indices have outperformed the S&P 500 over the past 6 months and 12 months (figures 1, 2). However, on a year-to-date basis, the S&P 500 has done better than the KOSPI but continues to lag the TWSE by a long way (figure 3).

Outlook depends on semiconductor cycle. The question now of whether KOSPI can return to outperformance – and indeed whether TWSE can continue this outperformance – will go to the semiconductor cycle. Taiwan Semiconductors and Samsung Electronics – respectively the largest and the fourth largest semiconductor producers in the world – are outsized constituents in their respective indices. While United Microelectronics has a smaller weight in Taiwan market indices, it is also a positive influence as the world’s second largest semiconductor player.

The global scramble for semiconductors. The ongoing growth in semiconductor demand is actually a continuation of a rising semiconductor cycle that started in 2019. Revenue growth q/q bottomed mid-2019. It was briefly interrupted in 2Q20, but is now resuming its upturn. Two factors have transformed a cyclical upturn into a scramble for semiconductors: 1) The pandemic has driven a surge in demand for consumer electronics and even automobiles, amidst an aversion to public transport – these are all driven by semiconductors. 2) Geopolitical tensions between the United States and China have prompted China to stockpile chips and chip-making equipment in the face of US technology trade restrictions. Bloomberg recently reported a 20% jump in China’s purchases of chip making equipment. Chinese imports of chips were reported to have risen 14% last year.

Supply bottleneck won’t change anytime soon. The manufacturing of semiconductors is an almost duopolistic situation for two countries – with Taiwan and South Korea reported to account for around 83% of world processor chip and 70% of memory chip production. Given the large capital expenditures and long lead times to add new facilities – up to 3 years to build a fabrication plant – the supply situation isn’t going to change much for quite a while to come. On the demand side, even if the pandemic-driven buying of electronics and automobiles eventually subsides, the structural drivers will persist. That is, the semiconductor content for each unit of GDP will continue to rise as automation and the “internet of things” gathers more momentum. This will be especially true for China, which is seeking to raise the quality of growth.

This cycle likely has another year of rising growth. On past cycles, the current cycle in semiconductor revenue growth probably has another year to run before the annual growth rate starts to ease. Then it could be another year after that before revenue growth goes into negative.

Longer-term trend – new applications will drive demand. As described by Deloitte in a 2019 report, beyond consumer electronics, the “next wave” of demand for semiconductors will be driven by emerging segments, particularly the automotive sector and artificial intelligence.

“In the automotive sector, the adoption of safety-related electronics systems has grown explosively,” said Deloitte.

“Automotive semiconductor vendors will benefit from a surge in demand for various semiconductor devices in cars, including microcontrollers (MCUs), sensors and memory. Automation, electrification, digital connectivity and security will result in the addition of more semiconductor content to automotive electronics and subsystems in the next decade.”

Meanwhile, “the AI semiconductor scene has seen a race not just at the application level, but also at the semiconductor chip level, where different architectures are vying for a piece of the pie. The cloud is the biggest market for AI chips, as their adoption in data centers continues to increase as a means of enhancing efficiency and reducing operational cost.”

Asia tech could get another boost if there is some accommodation between the US and China on semiconductors. News in recent weeks of the establishment of a joint US-China working party for the semiconductor industry is worth following closely. The China Semiconductor Industry Association (CSIA) and the US Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) last month announced the establishment of the US-China Semiconductor Industry Working Group on Technology and Trade Restrictions.

There has been media speculation that the establishment of this working group could pave the way for government-level discussions for an easing of the “tech war” that the US has been waging on China. Why would the US do that?

According to a report in the Atlantic Council: “China’s semiconductor import bill totals about US$300 billion a year, of which about US$75 billion came from US companies in 2018. Sales of equipment and materials for production increase that tally significantly.”

Meanwhile, the trade restrictions on Huawei and Semiconductor Manufacturing Industries Corporation (SMIC) “will incur costs for US companies while failing to ensure them supply chain independence,” said the Atlantic Council article.

“US policy instead must coalesce around a more nuanced effort to protect US technology and national security while leaving room for an essential industry to continue flourishing without sudden disruptions.

“Without a comprehensive national-scale effort to continue developing cutting edge semiconductor capabilities, the United States will be relying on global supply chains—and China—for many years to come, while firms incur the costs of global market disruption.”

“Meanwhile Premia Asia Innovative Technology ETF which covers most semiconductor leaders from Asia that are also world leaders in the space, would be a good allocation tool to consider for diversified exposure in this space”