Why US-China trade conflicts will continue

Resilient risk asset markets appear to be expecting the G20 meeting in Osaka to deliver some respite in the escalating trade war between the US and China. And it may do that. But even with a deal of some description, the conflicts between the US and China will likely continue to overhang the global economy for a long time to come.

The US-China trade spat thus far has been described as the early rounds of a 15-round fight to decide the world heavyweight champion. But it may turn out to be more a street brawl with neither time limits nor rules.

Containment not tariffs. Chinese officials have been at pains to make the case that the United States is not just interested in tariffs/trade – it wants containment of China. But they needn’t have gone to the trouble of elegantly constructed arguments. They only needed to quote the White House Director of Trade and Manufacturing Policy, Professor Peter Navarro, one of President Trump’s ideological soul mates and possibly inspirations.

His books “The Coming China Wars”, “Death by China”, and “Crouching Tiger” might be summed up as “darn right, it’s about containment.”

For example, in “Crouching Tiger”, he argued that “reducing the dependence of America and its allies on ‘Made in China’ products would seem to be an obvious step to improve both US national security as well as the prospects for peace in Asia.

“Whenever we buy products made in China… we as consumers are helping to finance a Chinese military buildup that may well mean to do us and our countries harm.”

Quoting University of Chicago professor John Mearsheimer, Professor Navarro argued that an “attractive strategy would be to do whatever we can to slow down China’s economic growth, because if it doesn’t grow economically, it can’t turn that wealth into military might and become a potential hegemon in Asia.”

So, it’s less about trade than about disengagement. It’s not about making the Chinese an offer they can’t refuse. It’s about making them an offer they can’t accept.

Remember Japan 1985? So, the Chinese are baulking at demands that include dismantling their economic model of “subsidising” State Owned Enterprises; changing its currency regime; and signing off on a list of legislations to effect structural changes demanded by the US.

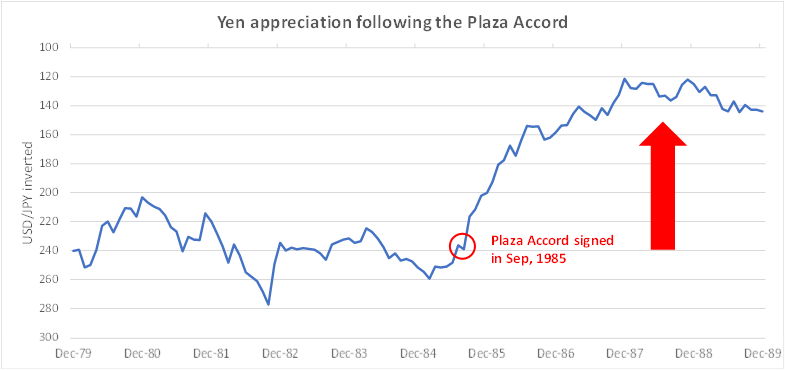

The Chinese would have noted that in the 1980s, the US initiated a series of protectionist measures against the Japanese, including tariffs, anti-dumping petitions, forced opening of the Japanese market, “Voluntary Export Restraint” (nothing voluntary about it but it was forced without formal agreement), and ultimately, via the Plaza Accord of 1985, massive appreciation of the Yen.

Former Japanese Prime Minister Fukuda Yasuo last year warned: “Japan had a large trade surplus with the US in 1980s, but a fast appreciation of Japanese Yen came after the US forced it to sign the Plaza Accord. The dramatic change brought huge negative impacts on Japan’s market, industries and economy. China should learn from this painful experience and stay vigilant and prudent.”

Mr. Fukuda was speaking the obvious to the Chinese.

Why the US’ structural demands might be unacceptable to the Chinese. 1) Legislating US demands might be seen as a humiliation by the Chinese, who are sensitive to historical “unfair” treaties with the West. 2) The dismantling of the whole State-led, State-owned, and State-subsidised economic structure challenges the Chinese Communist Party’s control over the levers of economic/financial power and hence its primacy. 3) Abandoning State management of the currency risks a Plaza Accord moment, something which should fill the Chinese with horror.

It might be easier for Beijing to accept the loss of 130 basis points of GDP. Oxford Economics has been reported estimating that a full-blown trade war – one in which the US hits all imports from China with a 25% tariff – would see China’s real GDP growth fall by 130 basis points in 2020. At the lower end of the range, HSBC Economics was quoted estimating a loss of 110-120 basis points. At the higher end, AXA Investment Managers was quoted estimating a loss of 150 basis points of GDP under the same scenario. Admittedly, this is “back of the envelope” stuff. Let’s just strike it down the middle of the range of 110 basis points to 150 basis points. Let’s say China loses 130 basis points GDP growth and ends growing around 5% a year. You have to suspect that Beijing might think it better to grit its teeth and take the hit, than to give up sovereign control over State Owned Enterprises, interest rates, and the currency.

Why the US may not back down either – it is confident in an apparently asymmetric battle. The White House might be thinking it has a stronger hand in this fight. Oxford Economics also estimated that should China retaliate in like manner – that is, impose a 25% tariff on all US goods – the US would lose only 50 basis points of growth in 2020.

The US would near-term also hobble Huawei. The Centre for Strategic and International Studies is reported to estimate that China is dependent on imports for 84% of its semiconductor needs. And of the 16% produced locally, only half are made by Chinese companies. The world’s top semiconductor companies are either American or based in countries very vulnerable to US economic, financial and political pressure. Think Taiwan Semiconductor, South Korea’s Samsung and SK Hynix, Japan’s Toshiba, and Dutch-headquartered and Nasdaq-listed NXP. And for China to produce its own semiconductors, it needs electronic design automatic (EDA) tools. And that industry too is dominated by US-headquartered companies Cadence (US-based and Nasdaq-listed), Synopsys (US-based and Nasdaq-listed), and Mentor (a subsidiary of Germany’s Siemens AG and headquartered in the US).

Further, this fight has gone from a “Trump project” to a “Team America project”. The Democrats have closed ranks with the White House on taking the trade fight to China. So, on the one hand, it empowers President Trump to play hardball with China. But it also limits the extent to which he can back down on his demands.

China is unlikely to implode. As written in an earlier Premia Partners Insight (here), the China collapse theory had long collapsed – it’s been 18 years since Gordon Chang published “The Coming Collapse of China”. The Chinese government has more policy ammunition than the US – in terms of potential interest rate cuts and government fiscal capabilities. China borrows overwhelmingly in its own currency. It has one of the world’s highest savings rates at 46% of GDP (which is the flipside of the high debt to GDP phenomenon). It has the world’s largest foreign exchange reserves. And it has capital controls.

Even hobbled by US tariffs and other restrictions, the Chinese economy could still limp past the US economy in about a dozen years. Even at 5% GDP growth, China will grow roughly the equivalent of the Australian economy as at 2018 in the two years from 2019-2021. And assuming long-term US economic growth of 1.5% per annum (it averaged around 2% over the past 10 years and could lose 50 basis points of GDP growth per year as a result of a full-blown trade war), China’s GDP could exceed the US GDP by around 2031. That’s in US dollar terms. It already is the world’s largest economy by a significant margin on PPP terms.

Hope for the best, prepare for the worst. So, the next critical event is the G20 meeting in Osaka where President Trump is expected to meet with President Xi Jinping. Three scenarios are 1) The two countries reach a limited agreement, with possibly a limited shelf life, covering purely tariff matters, agreeing to continue negotiating on the difficult issues of structural/regulatory change in China’s industrial and financial structure. 2) The US agrees to suspend the planned 25% tariff on another $300bn of Chinese imports, while talks continue. 3) Talks break down, resulting in a full- blown trade war.

The first two scenarios will give the risk markets a short-term reprieve, bearing in mind that they only buy more time before another day of reckoning down the line. Anyway, markets were not really expecting scenario #3 to begin with, as evidenced by the resilience of the US and European stock markets over the past 12 months, and the lack of safe haven Dollar buying over recent weeks. The final scenario would hasten the global economic slowdown and correct developed market risk markets down sharply.

All the above charts are sourced from Bloomberg, Jun 2019

Related Premia Partners tickers

High quality China A blue-chips: Premia CSI Caixin China Bedrock Economy ETF – 2803.HK

High quality China A new economy stocks: Premia CSI Caixin China New Economy ETF – 3173.HK

ASEAN as a trade war beneficiary: Premia DJ Emerging ASEAN Titans 100 ETF – 2810.HK / 3173.HK