Phase 1 is not even a trade war truce – it’s an agreement to contain the conflict. The US-China “Phase 1 trade deal” is an agreement to contain the current trade conflict. The two countries remain locked in trade hostilities – as evidenced by continuing increased tariffs – albeit at lower levels of intensity. They remain locked in broad-based strategic competition.

What’s the deal?

|

Expect more friction as President Trump goes into election campaign mode. Looking forward, investors should expect more turbulence on the trade front. Given President Trump’s track record for unpredictability and “out of left field” moves, investors should price some buffer for the probability of him revving up the conflict again, particularly if he needs nationalism-driven votes ahead of the November 3 Presidential Election.

The agreement on intellectual property protection and technology transfers is in some areas vague and open to differing interpretations. These could be sources of future tensions.

China buys more time to reduce its dependence on US technology and trade. China will use the time bought by the containment of the conflict to speed up its race for technology, trade linkages ex-the US, and domestic consumption/import substitution to lower dependence on the US.

Beyond the Chinese New Year handshakes, what next? China had maintained a studied silence while President Trump alternated between optimism, pessimism and threats in the negotiations.

China has agreed to buy more from the US. For China, that would be an acceptable, transactional solution to placate a famously transactional US President, except President Trump’s targets are extremely high for his time frame. (More on that later.) But for now, China’s agreement to the very ambitious import targets will buy it time.

China has agreed to abide by IMF rules against currency manipulation. This will not change anything for China’s currency regime as the US Treasury has just dropped its designation of China as a currency manipulator. In any event, currency stability also suits China given that an unstable/weak Renminbi had in the past encouraged capital flight. Yet, there are more difficult issues ahead.

China is unlikely to abandon subsidies for SOEs nor surrender control over the Renminbi. China is unlikely to hand control of its currency over to pure market forces. The currency issue will remain in the background as long as there is currency stability. China will continue with its existing currency regime and the US will stop calling it a currency manipulator.

China is just as unlikely to give up its State-led economic model. China will reform its SOEs on its own timetable. It is unlikely to be forced or rushed into giving up State ownership and subsidies. That has deep implications, right down to control of interest rates, and the relationship between household savings and SOE investments. Those are matters of national sovereignty.

China will remember the 1985 Plaza Accord and what that did to Japan. As a result of the Accord, Japan was forced at the point of a trade “gun” into a doubling of the Yen from USD/JPY 241 just before the Accord to 121 by end-1987. What followed was a chain of events which contributed greatly to the secular decline of the Japanese economy.

The Japanese economy slipped quickly into recession from late 1985 to early 1987. To counter the contractionary impact of a doubling of the value of the Yen, the Japanese government cut interest rates by 300 basis points and introduced a large fiscal package in 1987. However, that stimulus whipsawed Japanese assets into stock market and property bubbles in the second half of the 1980s, and a spectacular bust in the early 1990s. That was followed by decades of sluggish growth and eight more recessions between 1990 and 2018.

The Chinese have said it many times in different ways and via different channels – it won’t accept another Plaza Accord. This was summed up by China’s Ambassador to the US Mr. Cui Tiankai who said in 2018: "On what to do next, for China it is very clear. I wish to advise people to give up the illusion that another Plaza Accord could be imposed on China.” The Chinese would also have noted that the current US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer was the Deputy Trade Representative under President Ronald Reagan in negotiations with the Japanese in the 1980s.

An unsustainable conflict containment deal. This is an unsustainable “truce”, if you can even call it that. At best, this is conflict containment. Given that the Democrats have jumped enthusiastically onto President Trump’s China Containment bandwagon, it is unlikely the US will back away from its demands against State control of and subsidies to businesses in China. The apparently contradictory wording of the agreement on the currency will also keep this simmering in the background. And possible differences in interpretations on the agreement on technology transfers will also keep this issue alive.

Extremely ambitious import targets for China are likely to cause problems down the line. Worse, even the transactional appeasement of more purchases from the US looks mathematically challenging. Yes, it can be done, but only with a considerable time lag – not over two years – and at the cost of considerable destabilisation of trade flows around the world.

China imported US$179 billion in goods and services from the US in 2018. In 2017, the base year for incremental purchases, China imported US$190 billion in goods and services from the US. So, under this agreement, China has to grow its total imports from the US this year to at least US$267 billion – an increase of 49% over 2018. And in 2021, China has to import at least US$313 billion from the US – a further increase of 17% on the target for 2020, taking targeted imports from the US for 2021 to 75% more than in 2018.

Sure, China has suffered a 40% decline in its pig stocks, as a result of African Swine Flu-related culling. That has driven a spike in pork prices, which has fed into food inflation. So, that’s an easy one.

The world’s most populous nation, with a rapid consumption growth rate, can also build up stocks.

But a lot of this is going to be at the expense of China’s other trade partners. China will have to divert purchases away from countries such as Australia (energy and agricultural products), Canada (food and agricultural products), Brazil & Argentina (agricultural products).

China imported a total of US$126 billion in agricultural products in 2017. In 2018, China imported only US$13 billion from the US. Under this deal, China has to carve out around 10% of its 2017 global purchases to satisfy US demands for additional purchases in 2020. In 2021, China has to channel around 15% of its 2017 agricultural purchases to the US. Much of this will come at the expense of other countries. Yet, agricultural commodities are traded on contracts and not on a spot market and there are existing contracts with other countries.

As Deborah Elms, executive director of the Asian Trade Centre, said recently on CNBC, the Chinese have been “very cautious” in saying that they would buy according to market conditions and World Trade Organization restrictions. “In other words, there’s a giant red flag that says: even if we promise this ... be careful because if the market doesn’t support the purchases at that level, we may not reach that target,” she told CNBC.

China is likely to hold a steady monetary policy course to ride out the trade turmoil. Significantly, China has maintained a steady course on monetary policy through 2019 despite slowing economic growth and the trade war with the US. Indeed, it may be that China is moderating stimulus because of the trade and strategic tensions with the US. That is, it realises that imprudent stimulus will weaken rather than strengthen the economy over the long-run. China’s economic policies for 2020 should be seen through long vision lenses.

There have been many articles in the Chinese government-controlled media over the years highlighting the policy mistakes that led to Japan’s secular stagnation. As outlined above, the Yen appreciation forced by the Plaza Accord is often cited, as is the excessive stimulus that inflated asset bubbles.

China’s M2 money growth has been moderating. August 2019 over August 2018, China’s M2 grew 8.2%. On the same y/y basis, this is a further deceleration from 8.8% (12-months to August 2018), 8.9% (August 2017), and 11.3% (August 2016).

The People’s Bank of China recently said China would ensure that increases in M2 money supply and aggregate financing would be in keeping with nominal GDP growth, ruling out the possibility of "flood-like" stimulus. The 8% M2 money supply growth in 2019 was in keeping with this, given real GDP growth of around 6% and nominal GDP growth of around 8%.

Outstanding CNY loans growth remained at relatively moderate levels of around 12-13% through the course of 2019, compared to the peaks of over 15.5% in 2016.

Meanwhile, China’s crackdown on shadow banking continued last year, with rapid expansion peaking in 2017, going into contraction last year. In a report released September last year, Moody's Investor Service said broad shadow banking assets shrank by about RMB1.7 trillion in the first half of 2019 to finish at RMB59.6 trillion, the lowest level since the end of 2016. And with that, shadow banking assets fell to 64% of nominal GDP at 30 June 2019, from 68% at the end of 2018, and from its peak of 87% at the end of 2016.

A few years ago, Premier Li Keqiang said China was done with “flood irrigation” of its economy and would focus on “drip irrigation”. Looking back, he has been good at his word. Indeed, President Xi Jinping has cited control of financial risks as one of his three priority “battles”, along with poverty reduction and environmental improvement.

Read between the lines: China will accept moderately slower growth as it balances financial risk and environmental degradation (both of which come with very high growth) and poverty reduction (which would be compromised if there was a sharp decline in growth).

So, Beijing will stimulate the economy when needed to avoid a sharp economic slowdown. It has the fiscal and monetary means to do so as mentioned in an earlier article: The Chinese Economy's 5 Biggest Myths. But policy moves are likely to be measured and targeted rather than broad-based, “bazookas”. Sometimes thought by economists as “policy flip flops”, what Beijing is doing is more accurately characterised as slowing a huge semi-trailer by alternating between the brakes and the accelerator, to avoid jack-knifing and crashing the vehicle.

Geopolitical competition continues. Interestingly, Japan’s exports to the US was 17% of total US imports of goods and services at the time of the Plaza Accord (1985). China’s exports to the US in 2018 was also 17% of total US imports of goods and services. This is not a coincidence. The trade war is a manifestation of US efforts to not be overtaken by China economically. And with economic power comes military power and strategic dominance. And this is the thinking in the US.

As Dr. Peter Navarro, Director of the Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy for the Trump Administration wrote in his book “Crouching Tiger”: “In thinking historically about the strategic implications of China’s rise and growing size, consider this: At the start of World War II, the combined economies of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan were only half the size of the United States. If for no other reason than the sheer weight of its factories and work force, America thereby held the strategic high ground.”

On the other hand, the military spending trend lines of the US and China “are likely to cross in the not-to-distant-future as China’s GDP growth continues to significantly outpace that of the United States and as America’s economy continues to perform below historical levels,” Dr. Navarro wrote.

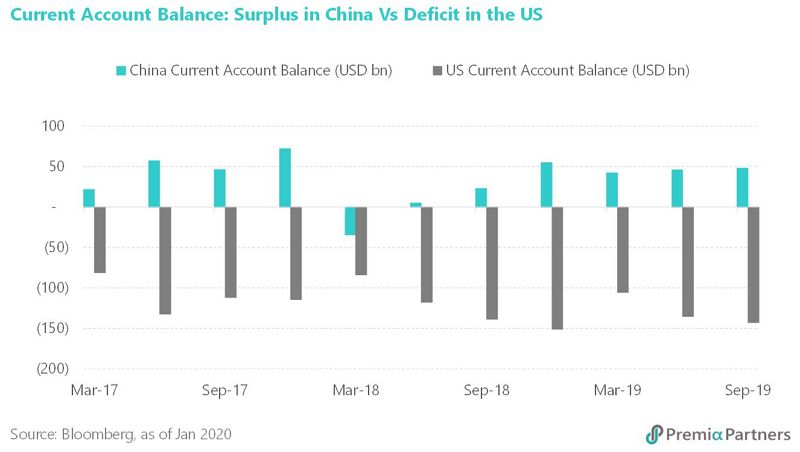

China’s long game. Interestingly, the US current account deficit has worsened since the start of trade tensions in 2018, while China’s current account balance – while volatile – has shown some overall improvement. These are the sums of total world trade relationships – overall economic and trade relevance – not just the bilateral between the US and China.

In this regard, China will race to build more trade alliances ex-US. As Michael Sampson from the Leiden University (Netherlands) noted, the ratio of intra-regional trade between East Asian countries alone has grown from around 25% in the 1960s to over 50% by the mid-2010s. With President Trump on the path of bilateralism and China championing multilateralism sans the US, China could reasonably expect to further reduce its trade dependence on the US.

While Beijing will tolerate slower economic growth, China’s GDP is still likely to overtake US GDP in US Dollar terms sometime in the 2030s as mentioned in an earlier article: The Inevitability of the Chinese Consumer. In tandem, it will also grow the consumption share of GDP to lower the economy’s dependence on exports.

Meanwhile, China will race to reduce its technology dependence on the US. For example, it recently announced a US$29 billion state-backed fund to develop semiconductor capabilities.

Former US Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson wrote last month in the Washington Post: “Beijing’s industrial policy and China’s private sector are racing to propel the commercialization of 5G and the technologies, products and services it enables, not only for China but also for nations around the world that would welcome Huawei 5G. Even China’s state-owned enterprises have deployed quickly. Meanwhile, Washington has stalled.

“Speed matters because deploying a reliable and secure 5G network quickly creates a first-mover advantage and results in the commercialization of myriad products and services. China could erect some 150,000 base stations by the end of the year, about 15 times what the United States will have.

“America has no domestic manufacturer of 5G equipment, so it must rely on European or Chinese suppliers. China already has Huawei and ZTE, the biggest 5G equipment suppliers in the world, allowing it to move to market quickly. In China, 5G is already available in more than 50 cities, while in the United States there is only 5G E, which is no substitute for a truly competitive 5G network.

“Erecting an economic iron curtain, as some policymakers are calling for, won’t halt Beijing’s progress — nor will it energize ours.”