RCEP – the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership – was finally inked on November 15, almost exactly nine years after it was first mooted at an ASEAN summit in Bali.

A World Bank paper estimated the deal could lift the collective GDP of members by up to 4.6 per cent by 2030. Beyond GDP gains, it will likely also boost economic specialisation within Asia, regionalisation of supply chains, and efficiency and productivity gains. Politically, the absence of the United States and India from the deal puts China at the center of an arrangement that will likely see the intra-regional share of trade exceeding the 65 per cent in the European Union. It will set precedents for sealing a North Asia free trade deal, involving China, Japan and South Korea.

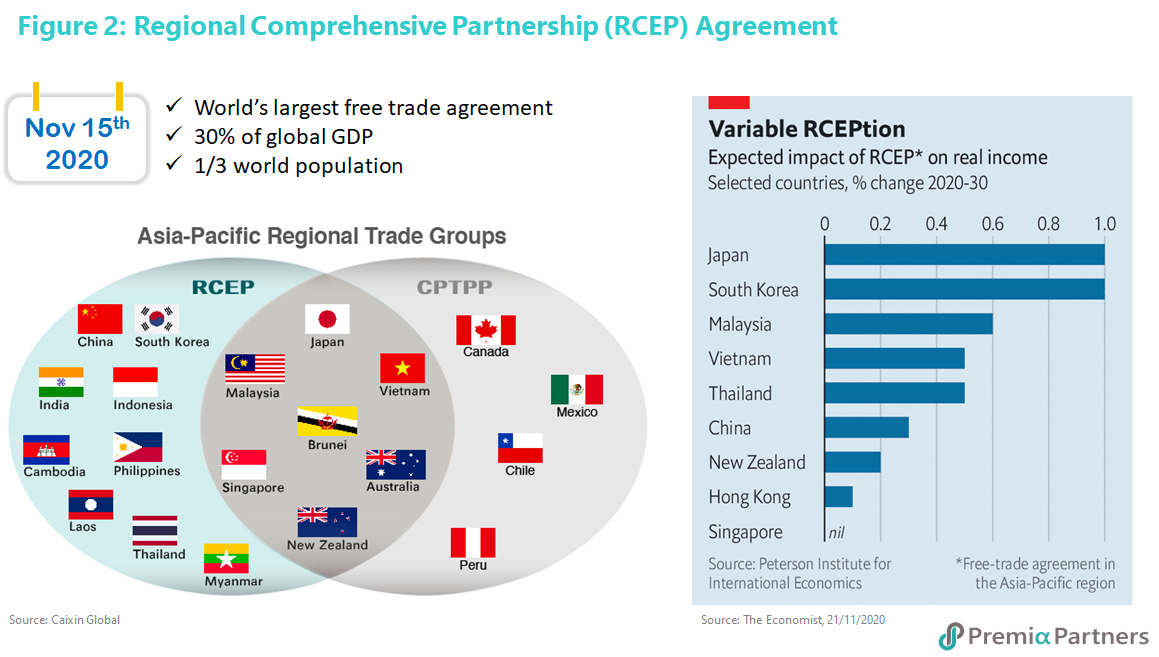

The biggest free trade agreement in the world – ever. This is a big deal. It is the world’s biggest free trade agreement, removing up to 90 per cent of tariffs for trade between 15 economies - involving 2.2 billion people, a combined GDP worth US$26 trillion, 30 per cent of the global economy and 40 per cent of global manufacturing. (The members are China, Japan, South Korea, the ASEAN 10, Australia and New Zealand.)

The GDP gains are significant. According to a World Bank paper produced late last year by Michael J. Ferrantino, Maryla Maliszewska and Svitlana Taran, RCEP should boost the overall GDP of its members by 1.5 per cent, before assuming productivity gains. However, its simulations assuming a “productivity kick” raised the GDP gain to 4.6 per cent by 2030.

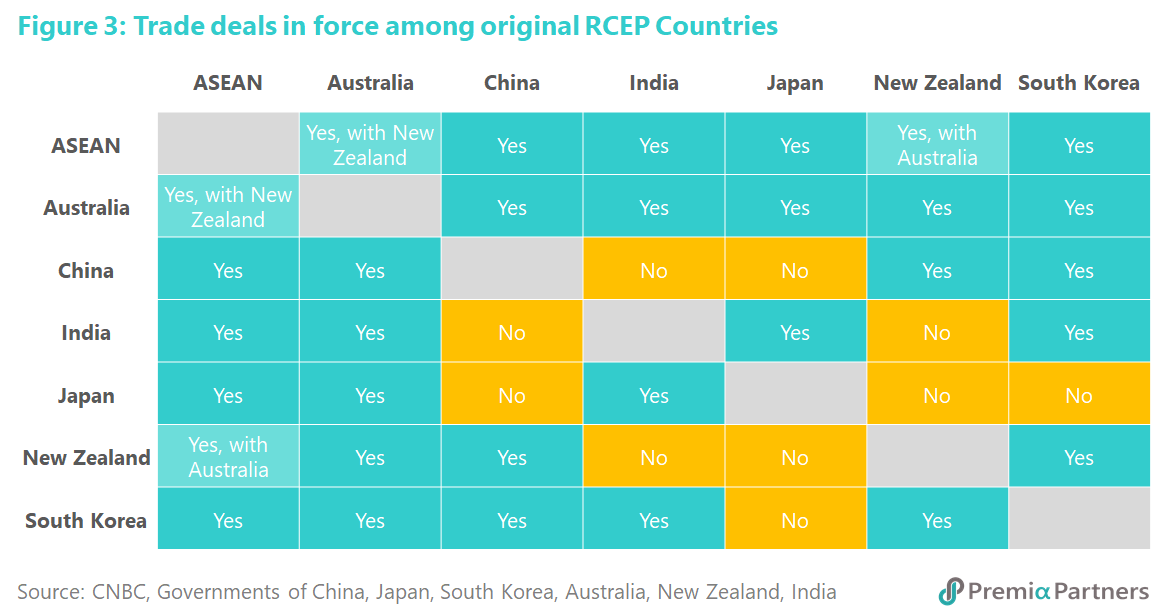

Accelerating the development of a China-centric regional economic order. Beyond GDP gains, it also pulls the region closer economically, with China as the hub. For China and Japan, it represents a de facto free trade deal between the world’s second and third largest economies that they had not been able to achieve bilaterally. It beats to the finishing post a proposed China-Japan-South Korea free trade agreement that had been talked about since 2002. It also sets the standards for an eventual trade deal between the three North Asian economic powers. Indeed, for China, Japan and South Korea, this is a big step forward. While there are many overlapping free trade agreements amongst other members of RCEP, this is a first for the North Asian trio.

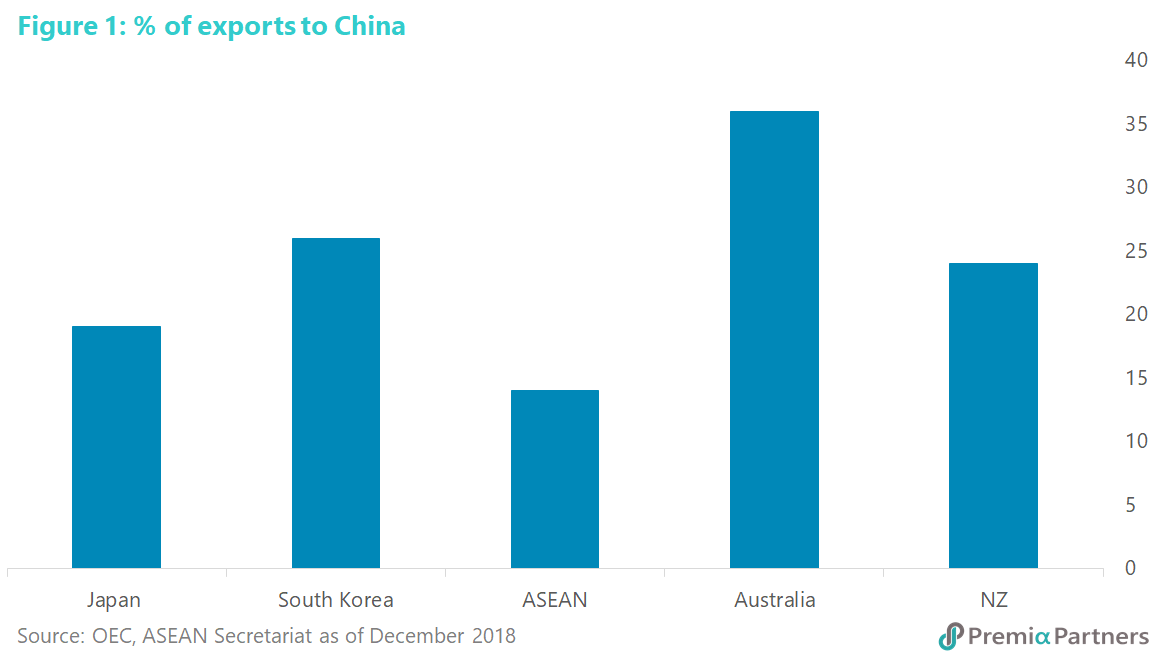

Intra-regional trade could hit 70 per cent of total trade in less than 10 years. The region’s export dependency on China is already clear – ranging from around 14 per cent for ASEAN to 36 per cent for Australia (figure 1). RCEP will deepen those relationships.

Intra-regional trade had already grown strongly from 45 per cent of total trade in 1990 to 60 per cent in 2019, at a time when intra-regional trade shares have been flat within the European Union and gone down in North America. Even before RCEP, Asia’s intra-regional trade share of 60 per cent had almost caught up with the 65 per cent for the EU. It is likely that with RCEP, intra-regional trade will rise to 70 per cent in less than a decade. Note the trajectory: Even without RCEP, the Asian intra-regional trade share had picked up 100 basis points a year, from 55 per cent in 2014 to 60 per cent in 2019.

Supply chain boost for ASEAN, tech boost for North Asia. RCEP will likely boost regionalisation of global supply chains, with ASEAN being a big beneficiary from companies relocating parts of their operations from China to avoid US trade barriers. So, over time, we are likely to see more final assembly in ASEAN with a lot of the intermediate goods flowing in from China. More foreign direct investment will likely follow the supply chains into ASEAN.

It will not just be Chinese companies moving parts of their supply chain out of protectionist harm’s way. It will also be driven by US and European companies doing the same. But now, RCEP will make it more likely that the upshot of US protectionism is offshoring ex-China rather than on-shoring back to the US. Indeed, by dropping out of the original Trans Pacific Partnership and hence paving the way for a China-centric RCEP, the US has facilitated the de-Americanisation of global supply chains.

Apart from eliminating tariffs, RCEP will also reduce non-tariff barriers by creating a common Rule of Origin, which will harmonise information and local content requirements for businesses trading within the RCEP region. According to trade credit insurance specialist Euler Hermes (a member of the Allianz SE group), the cost of rules of origin range from 1.4 per cent to 5.9 per cent of export transaction amounts.

“RCEP will therefore facilitate supply-chain management by requiring a unique certificate of origin to ship the same products between members. This would reduce transaction costs for trading with multiple countries in the wider region, and create a more stable environment for trade. As a result, not only should this agreement foster stronger regional trade integration, it could also make the region more attractive to further diversification of supply chains for multinational companies or multi-shoring.” it said.

Long-term, improved economic and intellectual property relations between China, Japan and South Korea could reduce China’s dependence on US technology. Generally, the long-term boost to the region’s manufacturing capabilities will mean lower reliance on the US for imports of tech and other high value-added products.

In a Peterson Institute for International Economics working paper, Peter Petri and Michael Plummer estimated that for China, Japan and South Korea, two-thirds of the new trade attributable to RCEP will be in advanced manufactures including electrical and electronic components.

They wrote: “Even without a trilateral FTA, China, Japan and Korea are complementary economies and already trade a great deal with each other. China is the largest trading partner of both Japan and Korea, and they are China’s third and fourth largest markets, respectively. Given their technological level, the three economies are also poised for additional, European-style trade in differentiated products, including especially intermediate goods. Moreover, they offer complementary skills and advanced technologies for integrated production networks. With US linkages in doubt, these links provide essential insurance for supply chains that depend on sophisticated inputs.”

Geopolitical implications. The original TPP – with the US at the center – was seen by some as a trade mechanism to limit China, which was not a party to the deal. Yet, the US dropped out. Likewise, the original RCEP was to have had India, which would have been a counter weight to China. But India dropped out. So now, China has become central to the new trade rules for the region. The US now has to find a way to deal itself back into the fastest growing region of the world – that is, assuming it even wants to do so. Meanwhile for the ASEAN countries, especially Vietnam, the “China plus One” story will become even more important. ASEAN will ride on the regional GDP growth trajectory, and benefit from faster growth of both inter-regional and intra-regional trade liberalization.