Initiatives outlined by the recent Politburo meeting will likely boost the economy through fixed asset investment and the multiplier effects usually associated with new home acquisitions. The “Urban Village Redevelopment” initiatives outlined at the Politburo Meeting of 25 July 2023 could potentially create new housing demand valued at over RMB 2 trillion per year and property fixed asset investment worth RMB 0.4 trillion per annum.

Apart from the direct economic stimulus from the boost to fixed asset investment, there will likely be multiplier effects from spending on consumer durables usually associated with home acquisitions – furniture, electrical white goods and other household items. Then there will likely be second-round economic benefits from the creation of infrastructure – e.g. retail and food outlets and public services such as healthcare facilities – around these redevelopments. Local governments will also likely benefit from the revenue raised from land sales. The relocation of former urban villages under redevelopment could also help absorb some existing developers’ inventories.

As we wrote recently in the insight piece Why China 2023 is not Japan 1990, China’s urbanisation in 2023 is at a level similar to Japan in 1960, leaving a huge amount of room for “catching up” to drive economic growth. China currently has only 64% of its population in urban centres, and that was where Japan was in 1960.

The Politburo’s renewed focus on the urban village could give greater impetus to earlier proposals. The Politburo meeting of 25 July 2023 re-emphasised promoting Chengzhongcun, or “Urban Village Redevelopment”. This was formulated in the “Guiding Opinions on Actively and Steadily Promoting Urban Village Redevelopment in Megacities and Supercities” (“Guiding Opinions”) and approved by the State Council of China on 21 July 2023. These initiatives are an extension of measures previously proposed in China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2020) to continuously improve urban space structure and living quality through shantytown redevelopment (“棚户区改造”). The Politburo’s renewed focus on this could give greater impetus to the earlier proposals.

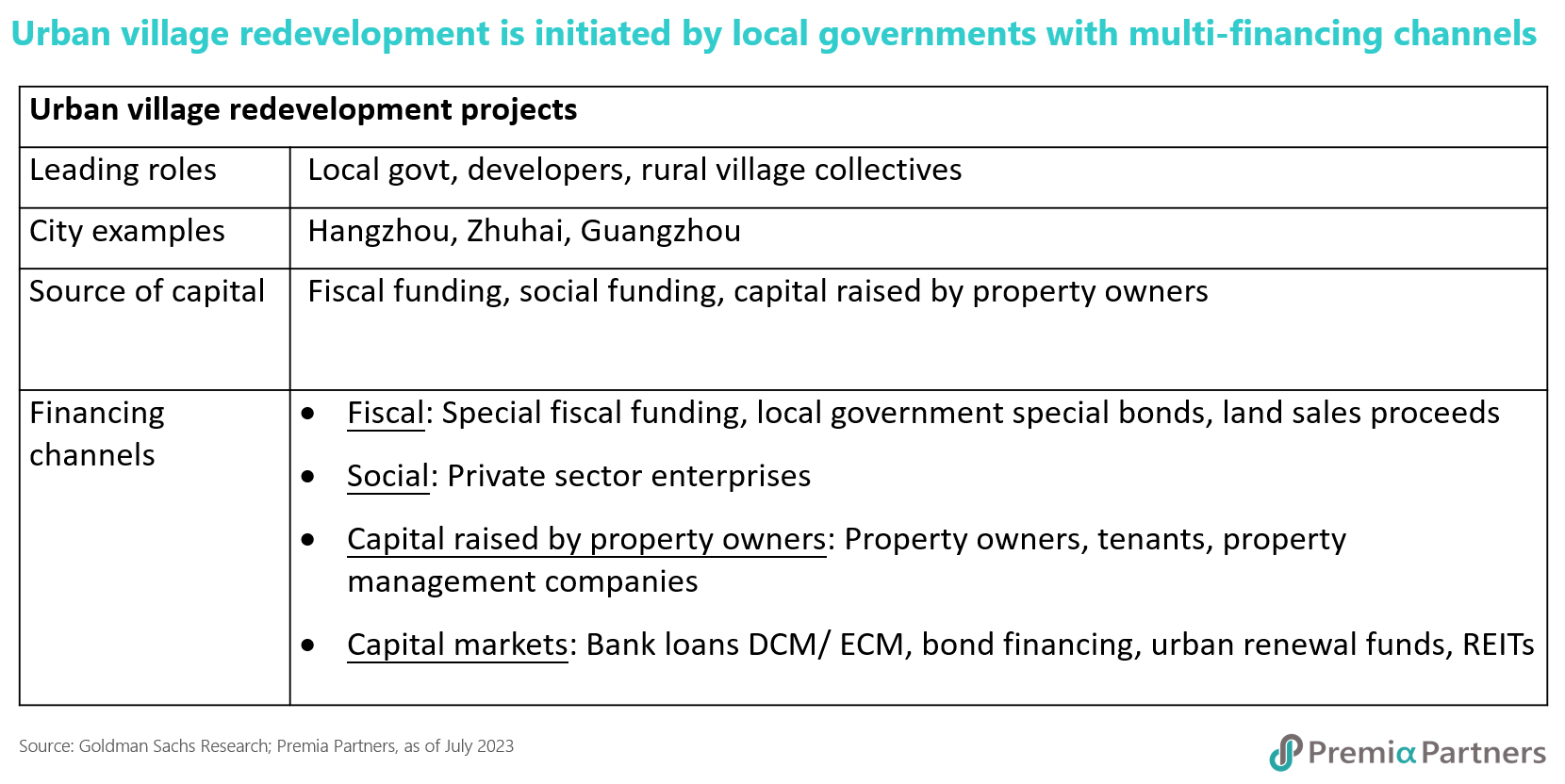

Urban village developments likely to involve multiple sources of financing, with private capital encouraged to participate. Compared to shantytown redevelopment which focuses on aged and obsolete buildings that need destruction and reconstruction, urban village redevelopment (“城中村改造”) targets village housing built on collective land located within urban areas that can be redeveloped via renovation and reconstruction. Although they both share the same vision, these two initiatives can differ significantly in terms of redevelopment models, capital sources, and their impact on the housing market.

- Lead initiative: Shantytown redevelopment involved state-led financing. Urban village redevelopment will however be led by local government initiatives, and multi-sources of financing especially private capital are encouraged to participate.

- Scope: Shantytown redevelopment focused on third- and fourth-tier cities nationwide while urban village redevelopment targets 8 megacities (with populations higher than 10mn people) and 11 supercities (with populations between 5-10mn people).

- Compensation: Shantytown land is mostly state owned, and residents are compensated financially. On the other hand, urban villages are mainly on collective land and owned by residents with rural “Hukou”. Former residents of areas under redevelopment could be compensated through re-housing vouchers "房票安置. These local government vouchers can be used as cash settlement for the purchase of alternative housing.

Improving the standard of housing and the quality of life for migrant workers. The rapid urbanisation in China over the past few decades has led to significant migration to super-large and megacities, continuous expansion of urban boundaries and soaring housing prices, which caused significant disparities in inner cities’ development. Urban villages attract lower-income groups such as migrant workers and junior white-collar workers, who seek commuting time efficiency. So, this initiative will address the issue of inadequate supporting facilities and improve the quality of life for young people and migrant workers.

The potential size of the population covered by such redevelopment is huge. The exact number of people living in urban villages in China has never been officially disclosed on a national scale. However, the Shenzhen municipal government revealed in 2022 that approximately 12 million people, accounting for 64% of the total population, live in urban villages.

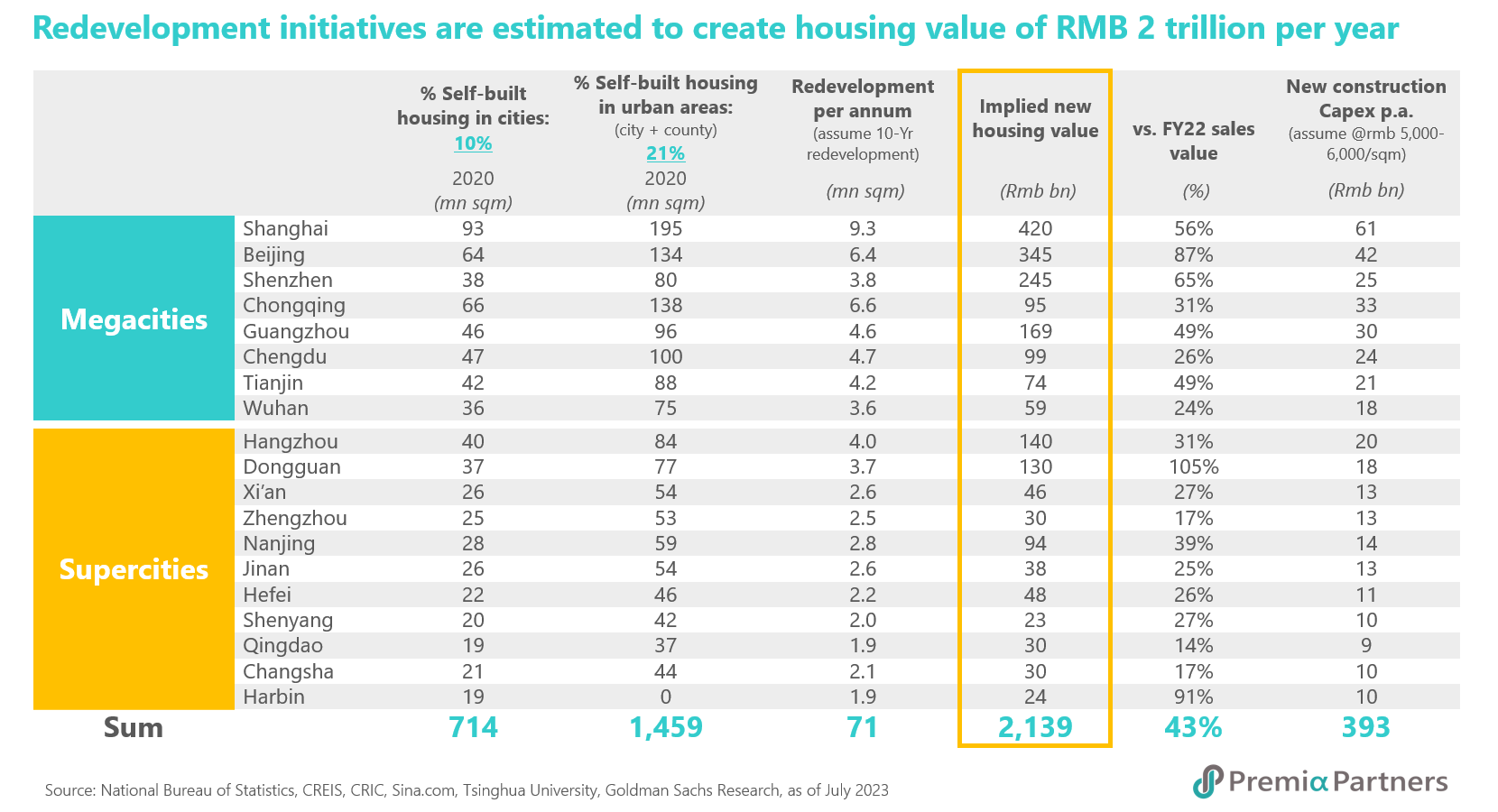

Implementation of the programme could span a decade. According to Goldman Sachs estimates, 8 megacities and 11 supercities together accounted for 22% of both the total urban population and housing stock as at end of 2021, as well as 38% of the 2022 financial year property fixed asset investment (FAI) and 37% of the national property sales value. As higher land costs in these cities and the challenges arising from legislative issues may slow the progress, the potential stimulus to FAI from new project construction in urban village land plots might span a decade.

Goldman Sachs estimates the urban village development programme could create housing valued at RMB 2 trillion per year and fixed asset investment worth RMB 0.4 trillion per year. With 714 million sqm of urban village housing stock in mega and supercities by the end of 2021, it is estimated that a 10-year redevelopment programme could create over RMB 2 trillion per annum in property value, which is roughly equivalent to 43% of mega and supercities’ aggregate total sales value per year. The new housing demand from former urban village dwellers could be met in multiple ways including public housing, relocation housing, public rental housing, existing commodity housing, inventory and newly built commodity housing from developers, etc. Over the long run, once new projects on urban village land parcels commence construction, an estimated RMB 0.4 trillion in new property construction fixed asset investment per year could be generated.

These new initiatives will likely drive demand for construction materials and household appliances, while also stimulating the development of public services such as healthcare, express delivery, convenience stores and other facilities – while it is also important to note the roles of technology and connectivity in such urban development especially since the pandemic, smart cities and green economy are the default configurations for China’s urban planning already. Our Premia CSI Caixin China Bedrock Economy ETF (2803), Premia CSI Caixin China New Economy ETF (3173) and Premia China STAR50 ETF (3151) given the policy alignment would be very appropriate tools to capture these related opportunities as China continues with its trajectory to build a ‘modern high-tech society’ promised in its 14th Five Year Plan.