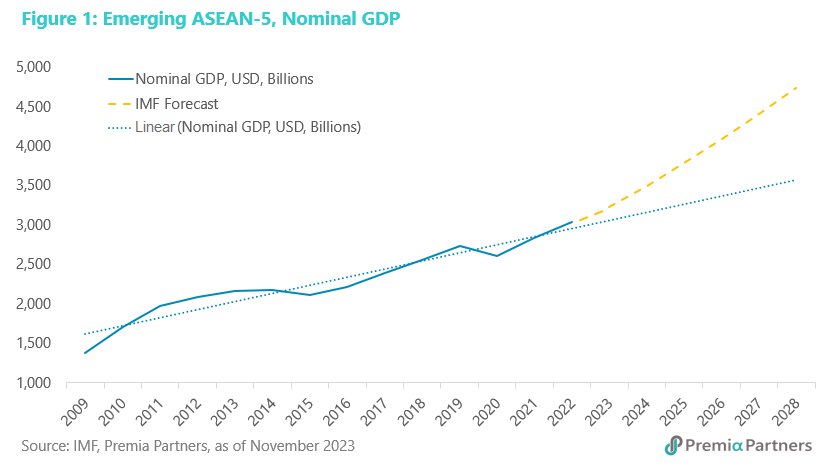

Emerging ASEAN-5 (Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, The Philippines and Vietnam) has broken above its nominal GDP growth trendline from 2009.

While many other economies have also bounced back to trend growth, the latest International Monetary Fund forecasts for the individual countries’ nominal GDP shows that collectively, the Emerging ASEAN-5 will likely have the strongest growth outlook among the major market/regional groupings. This is the conclusion from the latest individual country forecasts by the IMF and as collated by Premia Partners.

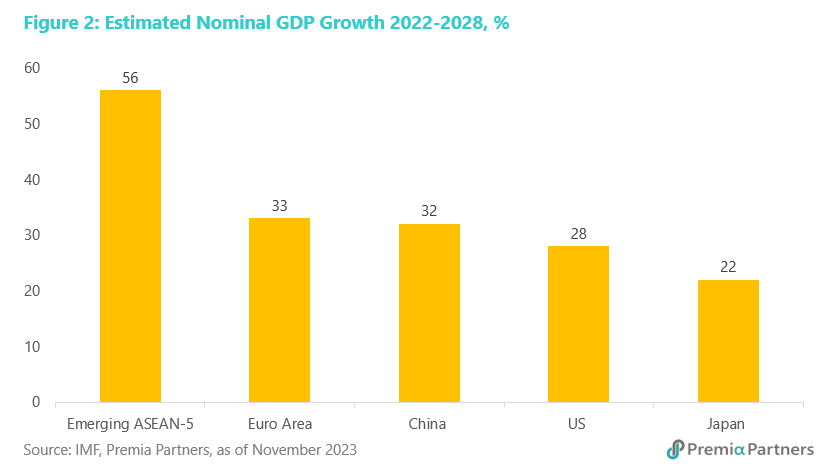

The IMF forecasts, which are up to 2028, suggest that Emerging ASEAN-5, will likely grow its collective nominal GDP by 56% between 2022 and 2028. Their expected gain will be way ahead of those estimated for the Developed Market economies of the US, Euro Area and Japan.

Both Emerging ASEAN-5 and the conventional ASEAN grouping are the world’s fifth largest economy currently, behind the US, China, the European Union and Japan. The IMF expects Emerging ASEAN-5 to grow its nominal GDP from 72% of Japan’s GDP in 2022 to 92% by 2028. Following the IMF’s forecast growth trends, Emerging ASEAN-5’s GDP should be neck-to-neck with Japan, for the position of the fourth largest economy in the world by 2030 and overtake it thereafter.

Premia Partners identifies the following drivers which will likely deliver this economic growth outperformance for Emerging ASEAN: 1) Positive spillovers from the China+1 supply chain construct; 2) Youthful demographics; 3) Urbanisation; 4) Relatively high levels of gross capital formation; 5) Per capita income catch-up; 6) Middle class consumption; 7) Expansion of the digital economy.

Emerging ASEAN as an extension of the “the world’s factory”. This is the China+1 construct that has been taking shape over the past five or so years. The idea that the West can “decouple” from China is fanciful. More likely, the changes will be at the margin, with that “margin” spilling over to Emerging ASEAN.

The statistics should speak for themselves. China accounts for 29% of the world’s manufacturing and has a long list of the world’s biggest producer titles, including electronics (35%), solar panels (80%), batteries (69%), electric vehicles (57%), motor vehicles (32%), chemicals (43%), ships (48%), textiles (50%), toys (70%), shoes (54%), steel (53%), and the list can go on and on.

Global supply chain diversification (China+1) and China’s own restructuring of its industrial base to push itself up the value chain will likely see more and more production relocated to Emerging ASEAN.

Labour cost comparisons are complicated, largely because of the lack of directly comparable data across different industries and different cities/districts within the same country, and differences in data definition/methodologies among countries. Yet, it would be widely accepted that Emerging ASEAN generally has lower labour costs than China. They are mostly lower in Indonesia, Vietnam and The Philippines, but are roughly comparable in Thailand and Malaysia. Data from countryeconomy.com suggests the minimum wage in Indonesia is 62% that in China this year; and Vietnam was 58% on 2022 data. In a similar vein, although different in the details of data collection, Statista said in 2018, Vietnam’s average manufacturing labour cost was 50% that in China.

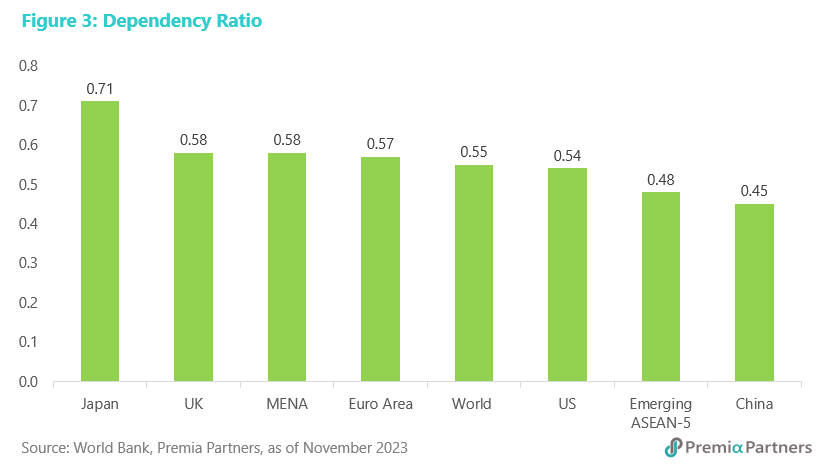

One of the most youthful populations in the world. Research by Premia Partners based on World Bank data suggests Emerging ASEAN has one of the most youthful (that is, largest working age) populations in the world, using the dependency ratio as a proxy. Indeed, it has the second lowest dependency ratio among the major markets/market groups, behind only China.

The dependency ratio measures the number of dependents – defined as those aged below 15 and above 64 – as a percentage of the working age (those between 15-64) population. In short, it is the number of dependents every 100 working age persons in the population have to support. So, the lower the dependency ratio, the bigger the working age population available to power the economy and fund things such as education, healthcare and social security.

Emerging ASEAN’s dependency ratio for 2022 was 0.48, significantly below the global average of 0.55. The dependency ratio for the US was 0.54; Euro Area was 0.57; Japan was 0.71. Among those major markets, only China had a lower dependency ratio of 0.45.

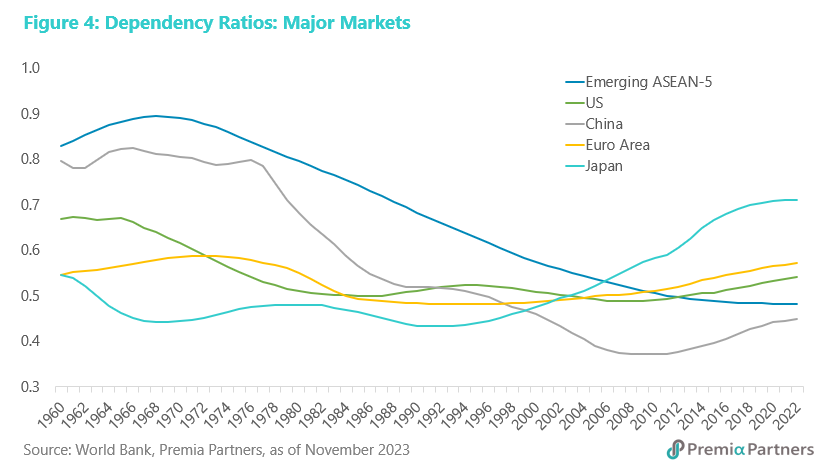

Also, significantly, Emerging ASEAN’s dependency ratio is the only one among the major markets that have yet to turn up.

For the US and the UK, the turning point was 2008; for MENA, it turned in 2012; for China, it was also 2012. For the Euro Area and Japan, the turning point came much earlier, around 1992.

For the US and the UK, the turning point was 2008; for MENA, it turned in 2012; for China, it was also 2012. For the Euro Area and Japan, the turning point came much earlier, around 1992.

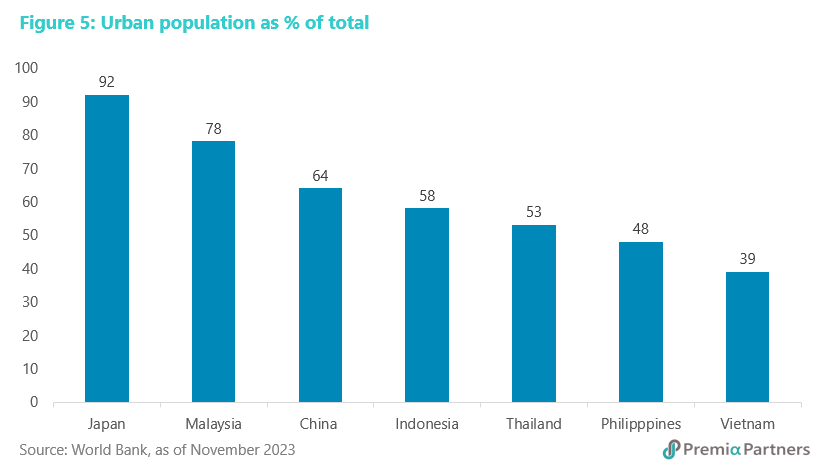

Urbanisation still has a long way to go to drive labour productivity and economic growth. Emerging ASEAN, with the exception of Malaysia (which has the smallest population amongst them), has even lower levels of urbanisation than China.

In Asia, excluding city state Singapore, the benchmark is Japan, where urbanization peaked at 92%. China is roughly where Japan was in 1960, with 64% of its population in urban areas. For Indonesia and Thailand, the comparable data for Japan would go further back in time than accessible from the World bank data base. For that, we refer to research by Kuroda Toshio, published in the 1986 book “Urbanization and Development in Japan,” which suggests Indonesia and Thailand are roughly where Japan was in around 1955. Vietnam would be roughly where Japan was in 1950.

As we wrote previously in relation to China, urbanisation drives productivity growth. The links between urbanisation and productivity growth are well documented. For example, the World Bank recently wrote: “With more than 80% of global GDP generated in cities, urbanisation can contribute to sustainable growth through increased productivity and innovation if managed well.”

Cities are hubs for information, knowledge, and education. In short, they are hubs for the development of human capital needed for productivity growth.

The expected higher incomes generated by urbanisation will then drive infrastructure development – everything from housing to transportation to utilities to retail to waste management.

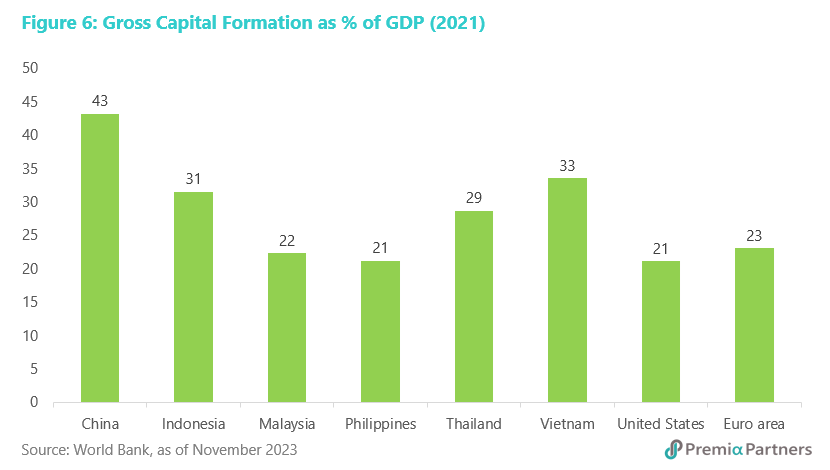

Healthy levels of gross capital formation. The figures bounce around from year to year. The big picture though is of comparatively healthy levels of gross capital formation as a percentage of GDP by international standards. Notably, Indonesia – the largest of the Emerging ASEAN economies – has seen a sustained surge in gross capital formation as a percentage of GDP since 2007. Vietnam has been running ratios of over 30% every year since year 2000.

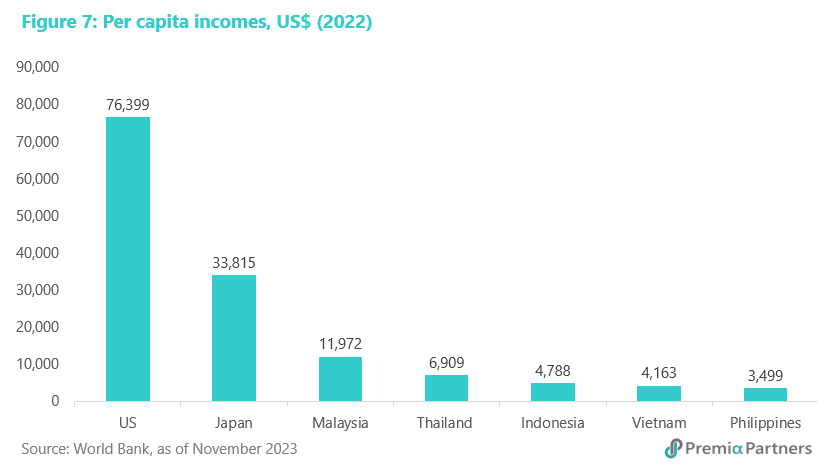

Relatively low levels of per capita income suggest a long runway ahead for high economic growth. In terms of the convergence/catch-up theory of economic growth – which argues for higher economic growth for lower income countries – Emerging ASEAN is a long way behind Developed Market economies.

Again, using Japan as the benchmark, Malaysia’s per capita income is at levels in Japan circa 1985; Thailand is around 1977; Indonesia is 1975; Vietnam is around 1974; the Philippines is around 1973. There is still a long runway ahead for rapid growth as lower income Emerging ASEAN accumulates more physical capital, lifts its human capital, and enjoys spillovers of technology from Developed Market economies and neighbouring China.

Explosive growth in middle class consumerism. This is the third most populous economy in the world, behind India and China. A 2021 Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) report suggests the “middle class” population in ASEAN has grown from around 40 million in year 2000 to 190 million by 2020.

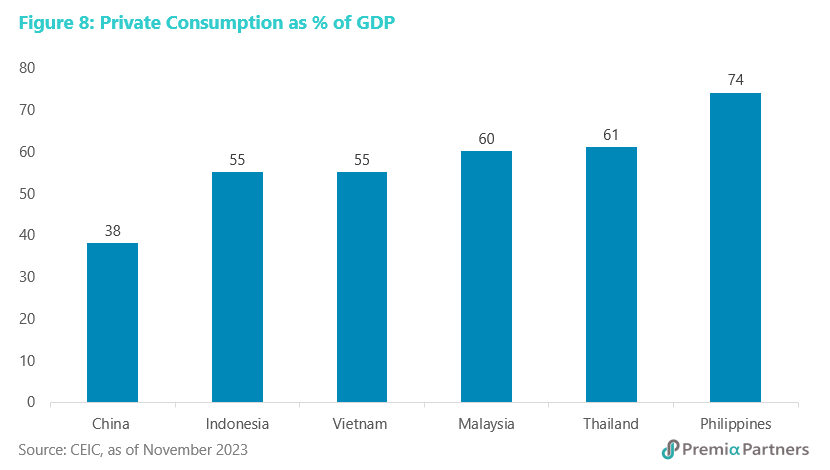

While it is playing catch up with China in per capita income terms (with the exception of Malaysia which is almost on par with China), Emerging ASEAN is different from China in one important aspect: It has a more robust consumer culture than China. Indeed, the contribution made by private consumption to GDP is approaching the level in the US (which is 68%) in Malaysia and Thailand, and has exceeded it in the Philippines.

We estimate that private consumption in Emerging ASEAN should be worth approximately US$1.8 trillion a year currently. Speaking about the more conventional ASEAN grouping, the World Economic Forum estimates private consumption could be worth US$4 trillion “over the next decade” – that is, by 2030. The report was written in 2020.

The report, “Future of Consumption in Fast-Growth Consumer Markets: ASEAN” said: “The highest increase in income will happen in Vietnam. There, the average disposable income per capita will rise from $2,000 to $4,000 by 2030, growing at an annual rate of 8%. That is twice the rate of the US. By comparison, Indonesia’s incomes will grow from $3,000 to $8,000 and the Philippines’ from $3,000 to $6,000 by 2030. By 2030, ASEAN will contribute 140 million new consumers, representing 16% of the world’s new consumer class. Many of these new consumers will be making their first online purchase and buying their first affordable luxury good. Further fuelling consumption will be a substantial expansion in the number of emerging ASEAN’s high and upper-middle income households, which will nearly double from 30 million to 57 million from 2019 to 2030.”

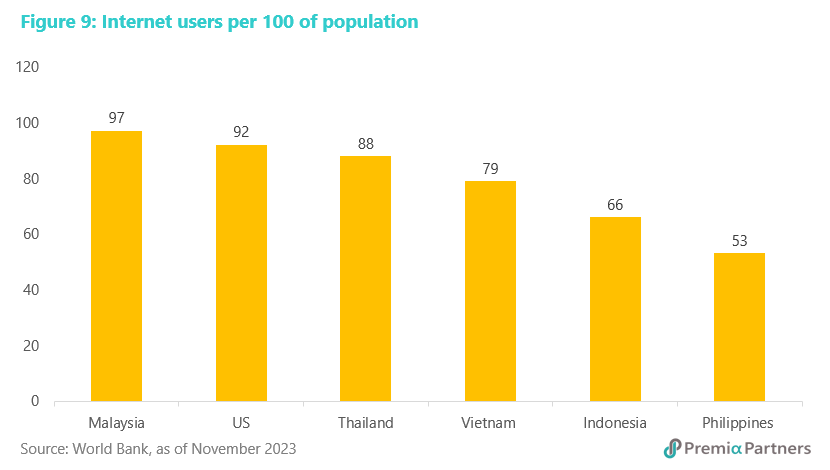

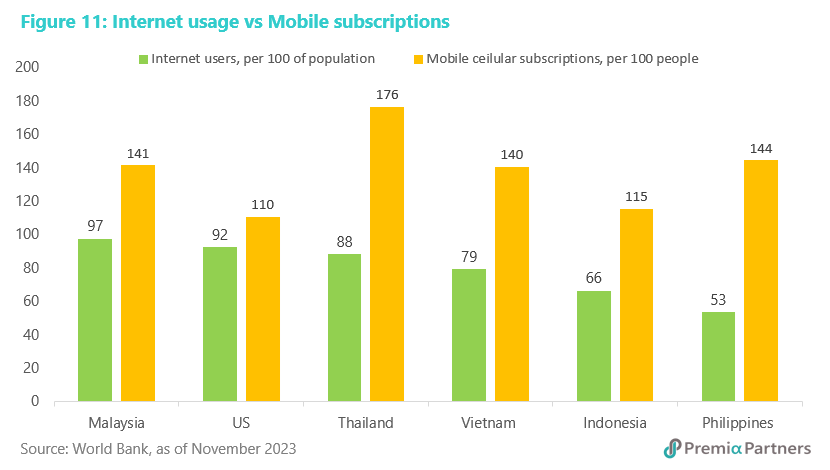

Leap-frogging the digital economy. Internet usage took off in the Developed Economies some 15 years earlier than in Emerging ASEAN, but the rates of internet users per 100 of population are converging, with Malaysia having even higher rates than the US.

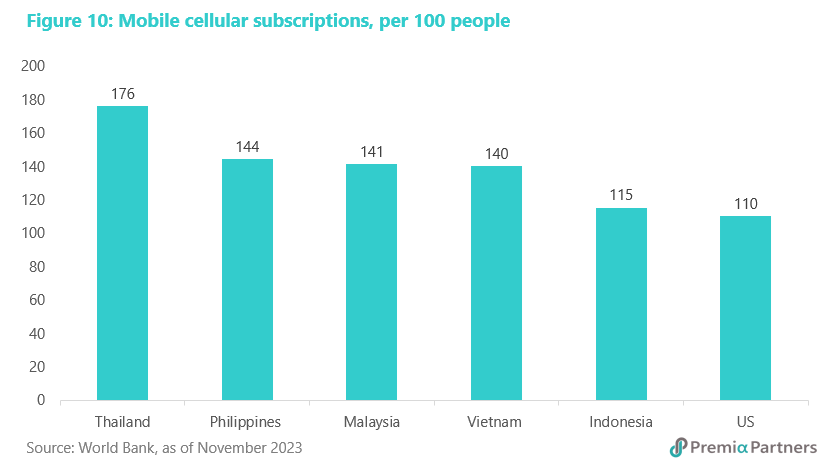

But the real story is in the technological leapfrogging of the Developed Market economies – apparently bypassing PC-based internet connectivity to mobile phone connectivity. Mobile phone subscriptions accelerated 10 years later in Emerging ASEAN than in the US, but subscriptions per hundred of population have now exceeded the US.

Mobile phone subscription data in Emerging ASEAN is interesting for another reason: Mobile phone penetration appears to be much higher than PC-based internet connections. We are mindful that the definition of internet users includes connection via mobile devices. Yet, even with that caveat, the remarkably high number of mobile subscriptions per 100 of population compared to the US suggests technological leapfrogging.

Technological adoption will help productivity growth, and by extension, economic and per capita income growth.

The ADBI report said the recent pandemic had accelerated ASEAN’s digital transformation and “may help ASEAN to bridge the infrastructure gap and the education gap and improve its market institutions and government efficiency and effectiveness…..”