The Great Transition Arrives

The US Federal Reserve has signalled the imminent start of the transition from the Great Stimulus of 2020-2021 to a period with new uncertainties.

In summary, the “bad news is good news” paradigm of the COVID-19 pandemic – under which disease and economic decline was good news for financial markets because they meant continuation of the greatest monetary and fiscal stimulus since the Second World War – will soon be over. In its place, we expect to see the gradual withdrawal of stimulus, slowing economic and earnings growth and higher inflation.

This will likely slow US equities returns to a crawl – investors have to be very selective, also likely pressure downward the value of US Treasury paper, and likewise edge down US corporate credits, albeit with a lag. The US Dollar though could stage a countertrend rebound in response to higher yields, that is, until much higher inflation erodes the real yields. Yet, that is a story for a more advanced stage of inflation, if we get there.

The Fed signals November taper at US$15 billion a month. The Fed’s suggested pace of tapering quantitative easing was at the high end of expectations.

There had been a range of forecasts in the market on the timing and pace of the taper.

At the very dovish end, there was the expectation of reductions of US$10 billion a month starting late this year to finish within 12 months (to run down the asset purchases from US$120 billion a month to zero). That idea was encouraged in part by the history of the US$10 billion a month pace of the last taper in 2014.

At the more hawkish end, there was the expectation of US$15 billion a month from late this year, completing by middle of next year. In between, there was the suggestion that the Fed could delay the taper, to start early next year, running at US$15 billion a month, completing sometime August to September next year.

The answer is out: unless there is a significant change in economic circumstances, we will get tapering from November this year, at US$15 billion a month, to complete by June next year. This is at the hawkish end of the range of expectations.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell said after the 21-22 September FOMC that tapering could start “as soon as the next meeting”. The next FOMC is 2-3 November. He also said: “Participants generally view that, so long as the recovery remains on track, a gradual tapering process that concludes around the middle of next year is likely to be appropriate.” The implication is the Fed planning to taper at US$15 billion a month, from November to June next year.

This is the “peak stimulus” component of the “triple peaks” in the US economy we wrote about on 18 August. https://www.premia-partners.com/insight/us-equities-the-challenge-of-scaling-the-triple-peaks

Watch the Treasury market’s reaction in coming weeks. The S&P 500 ended a volatile week (ended 24 September) slightly higher – rising despite the Fed indicating a relatively rapid pace for the tapering of its asset purchases.

However, we are wary about over-reading any “message” from the S&P 500 bounce after the FOMC. Near-term, it was technically oversold after 3 weeks of decline, and was due for a bit of a technical rebound anyway. We suspect – for both technical and fundamental reasons – this rebound won’t sustain, and we are in for a volatile October.

More importantly, we note that the US Treasury market continued to sell, pushing the 10-year yield into a technical “breakout”. In our Premia Weekly Digest email of 20 September, we warned of a developing ascending triangle pattern in the 10Y UST yield. We noted that this represented “coiled energy pushing up against the resistance at 1.38%. Usually, this is regarded as a bullish pattern, with a likely breakout above that triangle.”

So, last week, we saw a big break above that 1.38% resistance on the news from the FOMC meeting of 21-22 September (figure 1). The 10Y yield ended the week at 1.4526%, up from 1.3633% at the close of the previous week.

Our sense is that with tapering now almost upon us and inflation a clear and present problem, the 10Y UST yield will push higher over coming months.

The “VILE Economy” Redux?The Global Financial Crisis term “VILE Economy” – “volatile inflation, less expansionary economy” – has made a comeback in recent months, most notably in a speech by then outgoing Bank of England economist Andy Haldane. (Bit of history: The term surfaced in 2008, used at the time by Michael Saunders of Citigroup. Resolution Asset Management had a bleaker version called “VINE” – volatile inflation, no expansion – but its subsequent acquirer Ignis Asset Management also used the term “VILE” in later years.)

So, here’s our take on the “VILE Economy” 2022. The spread of the Delta variant has smashed hopes for a neat exit from the COVID-19 pandemic. It will now likely be a messy, desynchronised, 2-steps forward, 1-step back process. Even highly vaccinated societies are finding reopening fraught with surges in cases, threatening to overwhelm hospitals. So, we could find ourselves in a stop-start process of reopening around the world, as governments are forced to constantly calibrate the pace of reopening with an eye on available hospital beds. The slow vaccination of the Emerging Markets ex-China will add to the mess – worsening that desynchronised return to normality in different countries.

Economically, that means we are likely to see slowing economic growth beyond the “pop” that we saw earlier this year.

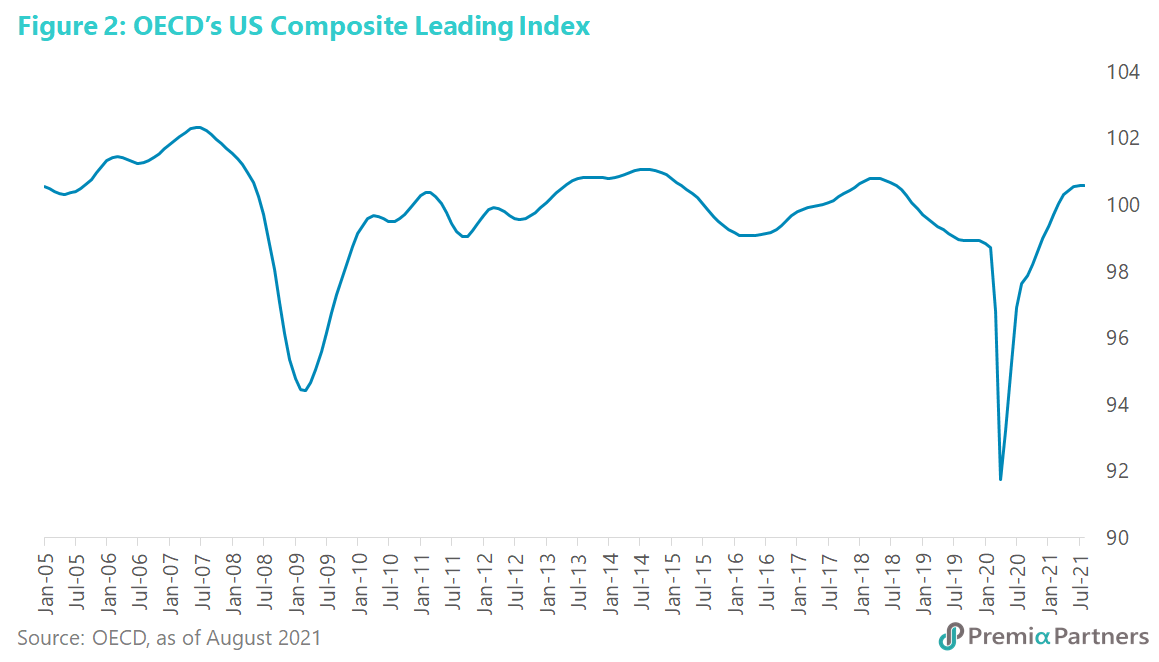

The loss of economic momentum is already hinted at by the flattening out of the OECD Composite Leading Indicator for the United States, from June of this year (figure 2). This is the “peak growth” of our “triple peaks” theme.

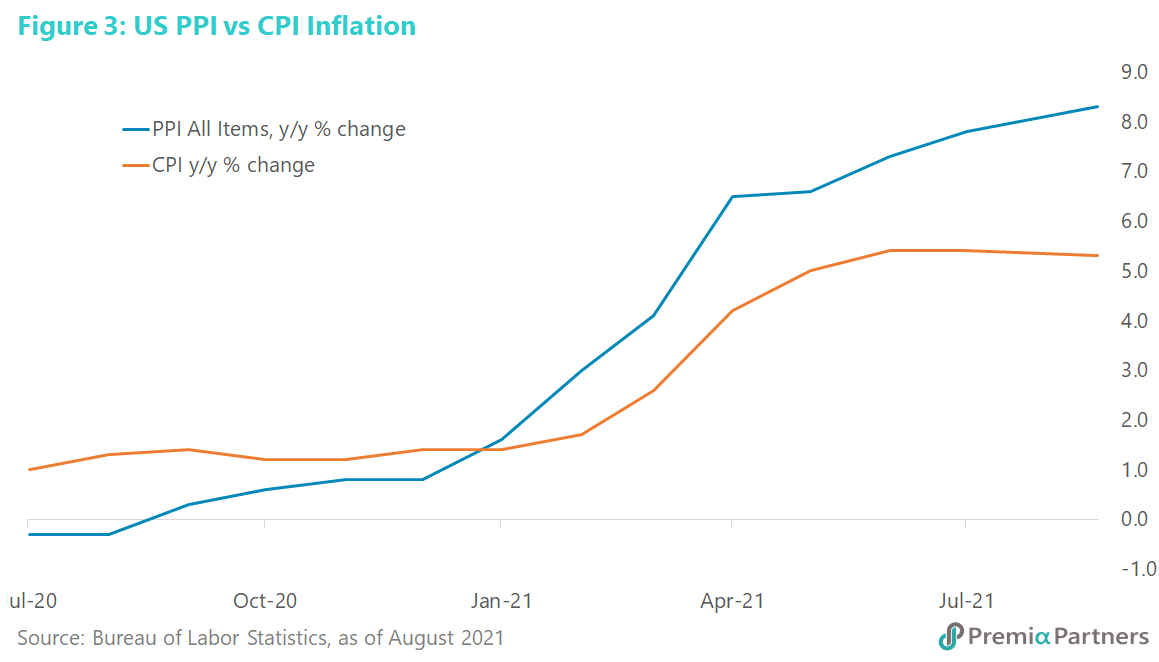

Inflation will put more upward pressure on US Treasury yields. The pause in the rise of US consumer inflation in July and August is unlikely to sustain. That flattening out of the US consumer price inflation data has to be seen against the backdrop of the relentless surge in US Producer Price Inflation (figure 3). Unless there is a dramatic downward shift in US producer prices very soon, consumer price inflation is likely to resume upwards led by producer prices. With energy shortages around the world – and surges in the price of oil, natural gas and even coal – and continued supply chain problems all over the world, that “transitory” inflation problem will likely worsen in coming months.

Unless there is a dramatic downward shift in US producer prices very soon, consumer price inflation is likely to resume upwards led by producer prices. With energy shortages around the world – and surges in the price of oil, natural gas and even coal – and continued supply chain problems all over the world, that “transitory” inflation problem will likely worsen in coming months.

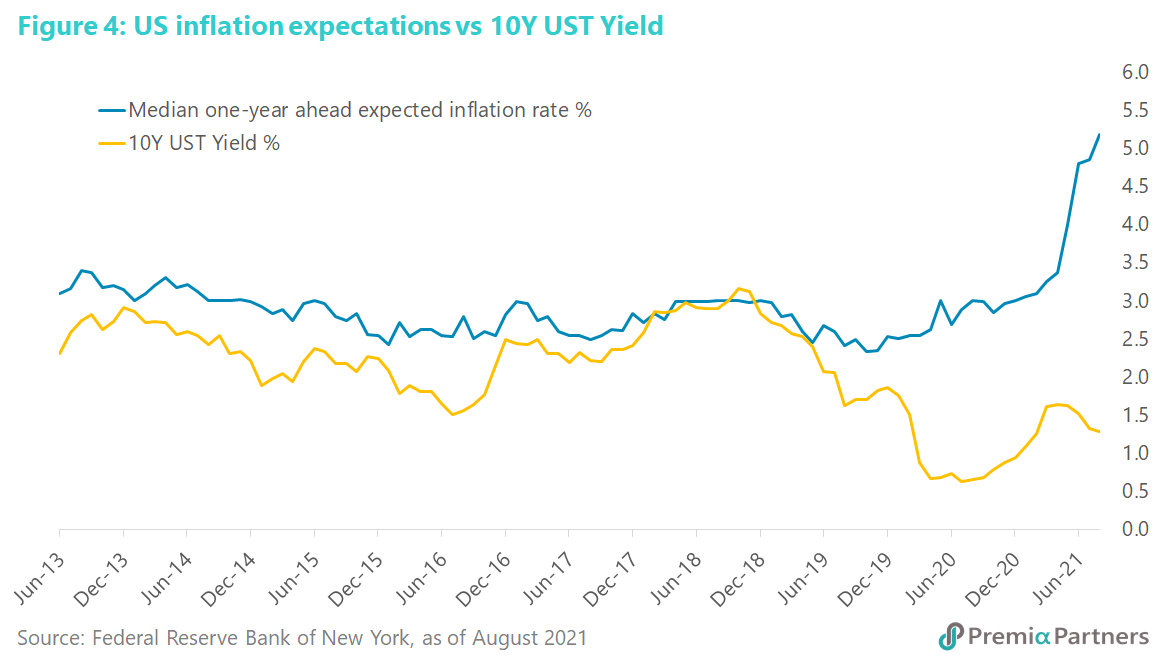

We also note the potential for inflation expectations to impact actual price outcomes. That is, if people expect prices to be higher in the future, it is quite rational behaviour to bring forward purchases before they become more expensive – a prime example being the stampede into residential property in many parts of the world since middle of last year. In this regard, the high inflation expectations of US consumers (as surveyed by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York) could feed back into consumer behaviour and higher inflation outcomes in coming months (figure 4). Note the link between US inflation expectations and the 10Y UST Yield.

Implications of the pace of the taper for interest rates. Mr. Powell repeated the message that “the timing and pace of the coming reduction in asset purchases will not be intended to carry a direct signal regarding the timing of interest rate liftoff.” But note that the median view of FOMC members regarding the appropriate Fed Funds Rate for 2022 has lifted from 0.1% at the June FOMC to 0.3% last week. That means the median view of the FOMC members is that the rates liftoff should happen next year. The market is viewing the pace of the taper as clearing the decks for a rates liftoff 2H of next year. That ticking clock – counting down the months before the rates lift-off – is not going to be helpful for equities.

US equities returns – expect low returns from here. In our 18 August Insight, we wrote: “Our sense is that we would either see small gains in coming months or indeed a correction in the face of the likely peaks in economic growth, earnings growth and policy stimulus.” The S&P 500 has traded sideways since 18 August, and is down slightly from the close of 17 August. We maintain the view that gains over coming months will likely be small, with growing risk of a significant correction. Given that tech stocks have a larger part of their valuations in more distant earnings, they will suffer more “duration risk” than stocks in the more “traditional sectors”. Therefore, we would also expect growth stocks to do worse in coming months than value stocks as peak stimulus gives way to the taper.

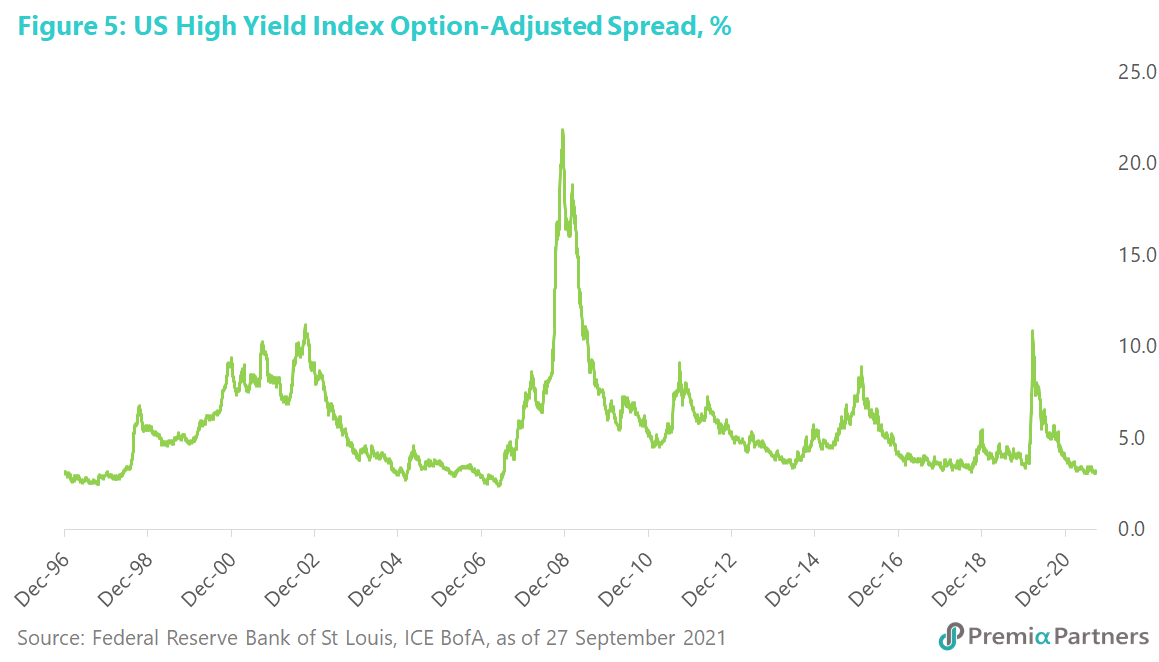

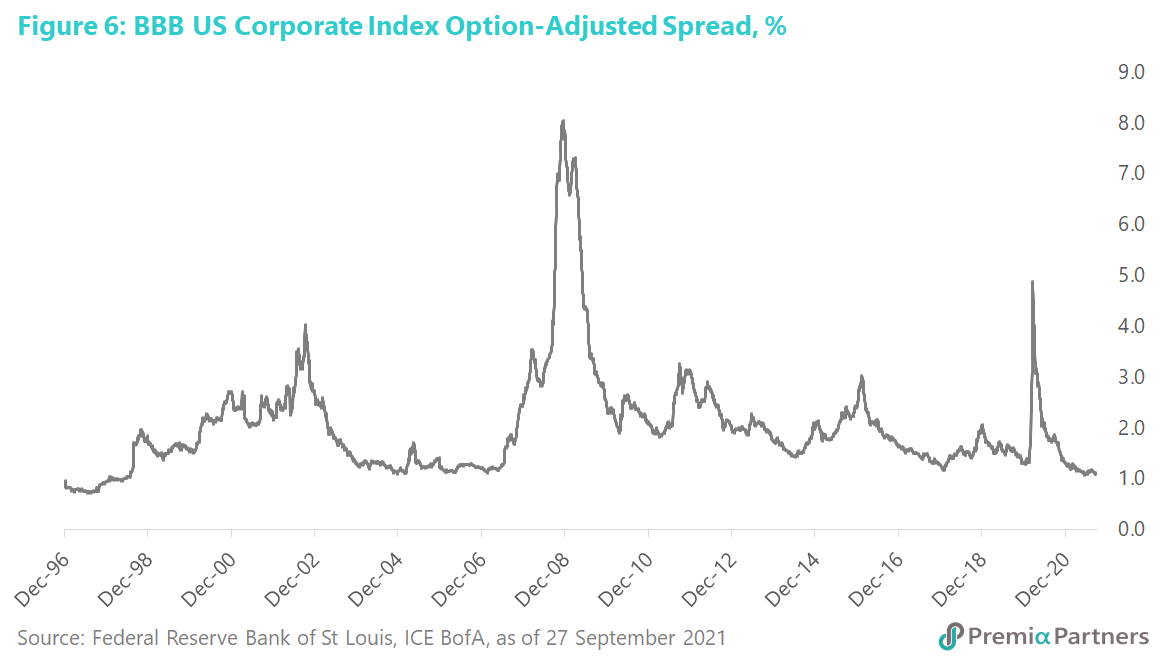

But the greatest risk is in bonds. A large part of the US bond market rally of the past 18 months has been the “buy what the Fed buys” theme. Gradually easing the Fed out of the market could also see gradual easing of price support from the market. 1.75% (which marks the March highs) is already in sight for the 10Y UST yield. If it breaks higher, things could get more frightening. Corporate credit spreads are so tight now and there is very little buffer for rising Treasury yields (figures 5, 6).