This is not about blame. The tensions between the US and China pre-date the Trump Presidency. Indeed, President Trump enjoys bi-partisan support on this issue. And China is not blameless either in the rise of those tensions.

Nevertheless, Donald Trump’s tactics for dealing with China has shattered a key principle underlying the post-1995 world trading system. That is the “most favoured nation” (MFN) principle that underpinned the idea of non-discriminatory trade. As the World Trade Organisation describes it, “countries cannot normally discriminate between their trading partners.”

“Grant someone a special favour (such as a lower customs duty rate for one of their products) and you have to do the same for all other WTO members.”

” It is so important that it is the first article of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade,” the WTO says.

We have seen that “Humpty Dumpty” moment in world trade and nothing is going to put it back together again.

In recently forcing Canada and Mexico to accept a clause that enables the US to scupper the USCMA trade alliance if either of the other parties enters a trade deal with a “non-market economy”, the United States has fired the starter’s gun on a race between itself and China in setting up competing trading blocs. Indeed, China could not have missed the significance of that precedence, as a template for other trade deals with Asian economies ex-China.

Not only are the gloves off, the knuckle dusters have come on. Never mind the non-discriminatory intent of the MFN article of GATT. This clause forces other USCMA signatories to discriminate against China.

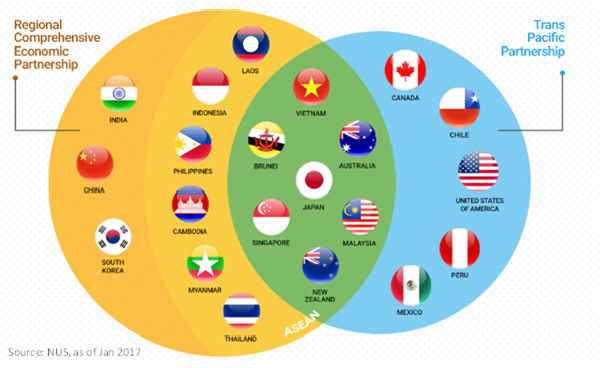

So, China is now pushing for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) as a nucleus for its own sphere of trade influence. RCEP, if completed as intended - involving the 10 ASEAN economies, China, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia and New Zealand – will form the world’s largest trading bloc, making up a third of the global gross domestic product.

Even if the trade dispute eases over coming months, China is unlikely to ease up on its efforts to build its own trade sphere of influence. It would likely see any easing of tensions as buying time to build its defences against any repeat of the assaults of the past year.

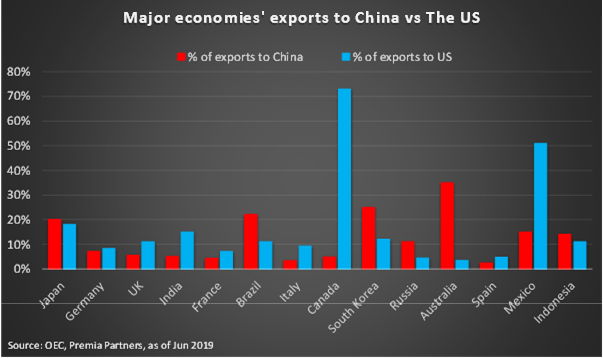

China’s influence in the region is considerable and rapidly growing. China is the largest destination for ASEAN’s exports outside the regional grouping, slightly ahead of the United States. It is similarly the largest destination for Japanese exports, again slightly ahead of the US. China is the most important export destination – by a huge margin over the United States – for South Korea, Australia and New Zealand.

China is also the largest source of extra-ASEAN tourist arrivals in ASEAN. Leaving aside trans-Tasman travellers, the Chinese are the biggest source of tourists for Australia and New Zealand, too. The Chinese are also the largest source of tourist arrivals in Japan.

Yet at this stage, China does not have enough trade muscle to demand its key trading partners to rule out trade agreements with the US. But conversely, ASEAN is not in the same position of overwhelming dependence on the US for its exports as Mexico and Canada are. So, the US has way less leverage to demand a veto over ASEAN trade deals with China. Anyway, RCEP would rule out that possibility, just as the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement had. So, there could be overlaps between US and Chinese spheres of influence.

One thing is much clearer. Whatever Donald Trump does to the global trade architecture, it is unlikely to reverse the globalisation of production. We are at least half a century past the era when trade comprised largely of finished products. With the emergence of emerging market manufacturing capabilities, global corporations have disassembled their production, outsourcing according to comparative advantage. The “centre” creates value through technology, design and branding. The “periphery” puts it all together at the lowest cost available globally.

So, for example, the New York Times last year quoted Tech Insights’ estimate of $443 to manufacture the Apple 256GB iPhone XS Max – which was then retailed at $1,249. It would have seemed a very sensible arrangement for Americans, for the US to then sell the phones made at $433 back to the Chinese at huge margins. However, apparently, President Trump disagrees.

But what can Donald Trump do to get Apple to sacrifice that margin? And how much more would US consumers be prepared to pay to give Apple anything near that kind of margin producing in the US?

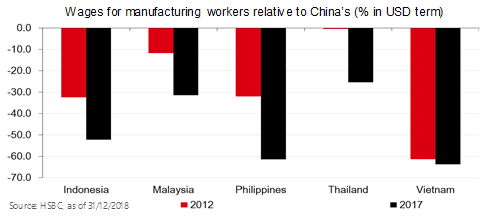

No, the more likely outcome would be for corporations to reconfigure their global supply chains to avoid US tariffs on “Made in China” products. Chinese manufacturers will do the same. They will likely move production to other countries in the region, with ASEAN the most likely destination, given its proximity, the availability of skilled labour, and relatively low costs. So, Chinese manufacturing will be forced to restructure towards higher value areas of production, which it had to do sooner rather than later anyway, given rising costs of land and labour in China.

ASEAN is an obvious beneficiary.

Independent research house TS Lombard cited the example of how Chinese manufacturers avoided US levies imposed on solar panel imports in 2012 by moving production to Malaysia and other Asian economies.

TS Lombard pointed out that the share of Chinese solar panels in US imports fell from 69% in 2011 to 11% in 2017. However, US imports of solar panels from Malaysia and other Asian countries jumped to slightly more than 50% of total US imports from near zero in 2011. It estimated that 60-70% of those sales were from Chinese companies which shifted operations to those countries.

Something similar may be happening in Vietnam now. US imports from Vietnam surged by nearly 40 per cent in the first four months of this year compared to the same period last year, according to a Financial Times analysis of data from the United States International Trade Commission. Over the same period, US imports from China fell by 13 per cent, the second-largest contraction since 2009.

The Asian Development Bank estimated that Vietnam could gain up to 2% of GDP (cumulative) over 3 years if the US-China trade war escalates, said the Financial Times.

Of course, the US could target Vietnam with tariffs too. But that would be like playing “Whack a Mole” – another low-cost emerging market production base would pop up, most likely in another ASEAN country. The US could then target ASEAN, and on and on that game goes, until Donald Trump pushes US productivity into negative growth while prices go soaring. Stagflation.

Meanwhile, companies which produce in the US for the Chinese market will be looking to evade Chinese retaliatory tariffs by moving out of the US – most likely to either China or ASEAN, depending on costs, the availability of skills, and supporting industries.

Related Premia ETF tickers

ASEAN as a trade war beneficiary: Premia DJ Emerging ASEAN Titans 100 ETF – 2810.HK / 3173.HK