Dollar weakness in the midst of the COVID Crisis may be a signal of worse to come. A major surprise in financial markets in the midst of COVID-19 has been the weakness of the US Dollar. Except for a 10-day period from 10 March-19 March, the DXY has been in retreat, falling around 5% from its 20 March high to the 10 June low.

That was because of the massive amounts of liquidity provided by the Federal Reserve through quantitative easing on steroids, splashed around the world through the Fed’s Dollar swap lines with other central banks.

Yes, that did the job of stabilizing the financial markets. Equities surged, corporate credit spreads tightened, and importantly, the Dollar weakened, and that Dollar weakening is more than just a by-product of the Fed’s action. It was likely the intended transmission mechanism of its stimulus plan.

1) The weakening of the Dollar helped offset, to some extent, the massive deflationary pressures on the US.

2) At the same time, it took Dollar funding stress off a selected group of countries. (Interestingly, the People’s Bank of China, the central bank for the world’s second largest economy in US Dollar terms, is not on that list of swap line counterparties. But that’s another story.)

Stimulus and currency debasement - two sides of the same (US Dollar) coin. The easing of Dollar funding stress as a result of the Fed’s mega-stimulus programme is the opposite side of Dollar debasement. Print, spend, splash it around the world and weaken the Dollar.

Consider how much the Fed’s balance sheet and US money supply has gone up by since the start of the year. US M2 money supply has gone up 20% in just 6 months. Also, the Fed’s balance sheet went up 70%.

Even after such a long period of monetary expansion – quantitative easing from 2009 – these are extraordinary numbers. It will come at a price. Indeed, that “price” may well be intended and necessary if the US is to have any chance of repaying its rapidly mounting debts. That is, a severely weakened currency and higher (imported) inflation is a means to dwindle down the real value of debts by Dollar depreciation.

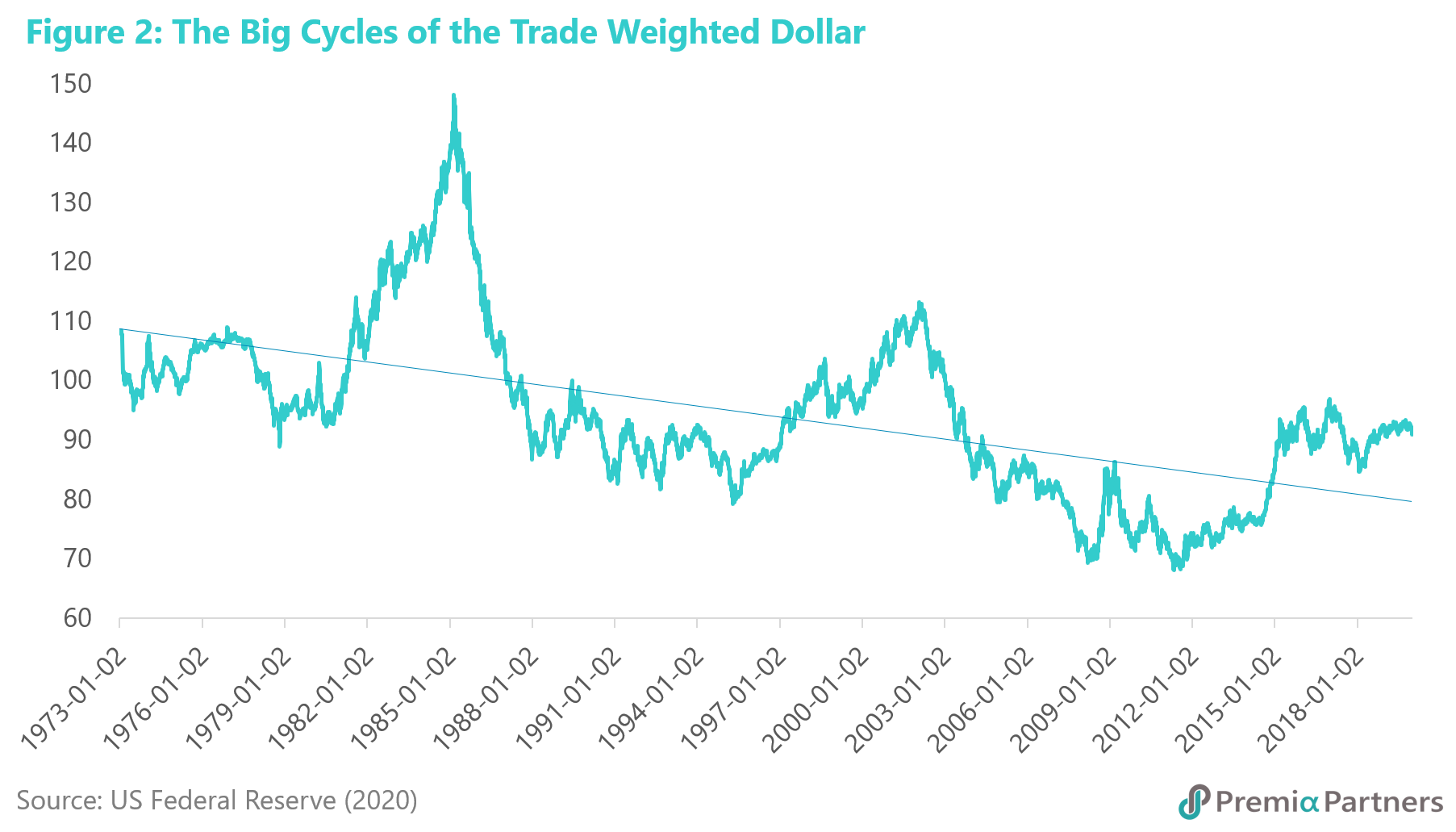

The big cycles in the US Dollar – we have started the next cycle, down. The US trade-weighted US Dollar runs in long cycles up and down. (Figure 2) Yet, the trend over the past three decades has been lower highs and lower lows after each cycle.

The upward cycle of the trade weighted Dollar which started mid-2011 may have ended 2Q2017 and we may already be past that 2-3 years of sideways drift we had seen in between previous cycles.

Pandemic policies may have been the watershed. US policy choices amidst Covid-19 could have triggered the move from sideways drift to structural decline. In particular, its decision to stimulate and reopen, instead of curbing the pandemic first will be very expensive.

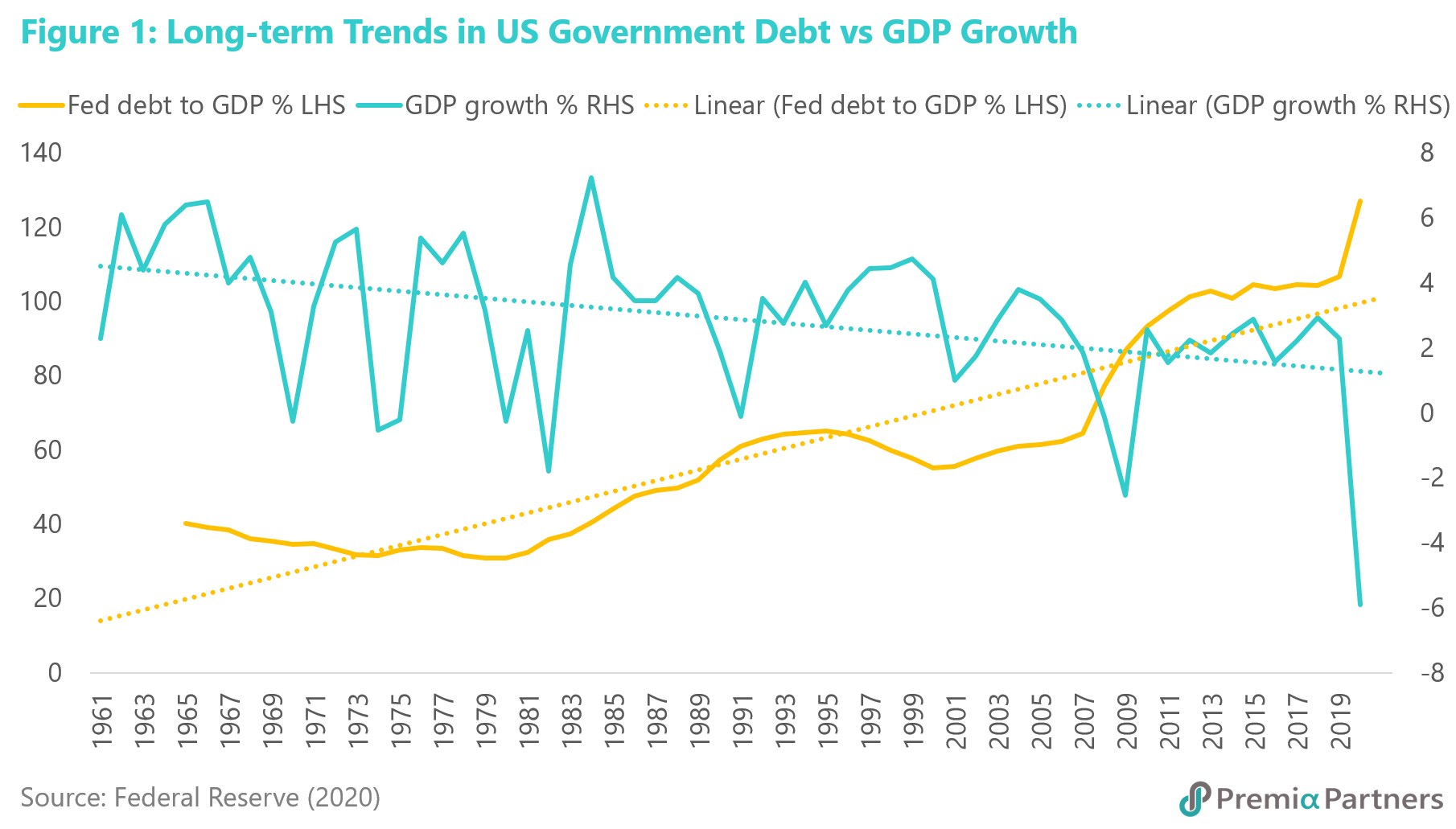

Huge debts will weigh on economic growth for decades. Spending big on misery alleviation (rather than curbing the spread of the virus) will push the US into a budget deficit of around 18% of GDP, according to the US Congressional Budget Office (CBO). That will be the biggest deficit relative to GDP since the Second World War. Federal debt to GDP has just surpassed that ratcheted up by the Second World War.

The surge in US government debt will weigh on economic growth for decades to come. That broad inverse relationship between government debt and GDP growth has been decades past in the making. The US’ pandemic policy choices will likely accelerate that trend. (Figure 1)

Given the size of the shifts in government debt and monetary expansion, this could be a historic moment of accelerated weakness in both the US Dollar and its economy.

Modern Monetary Theory – that “funny money” exercise of the central bank printing fiat money to finance government overspending – is almost reality in the US. Almost, as in, both the Fed and Treasury are still pretending they act independent of each other and the debt will be eventually repaid. When the market stops believing that, the consequences for the Dollar will be catastrophic.

Expect 6-7 years of decline in the Dollar. Beyond the acute phase of the pandemic, we could see 6-7 years of Dollar weakening against major currencies from here.

Stephen Roach, former Chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, drew gasps when he told CNBC last week that he expected 35% decline in the value of the Dollar against major currencies.

Yet, looking at the previous two cycles, Mr. Roach’s forecast is actually below the low side of the range. In the 7-year downward cycle from 1Q85 to 3Q92, the trade weighted Dollar fell around 45%. In the 6-year decline from 1Q2002 to 3Q2008, the trade weighted Dollar fell around 37%. (Figure 2)

Over the longer-term, the Fed is unlikely to be able to hold down corporate credit costs. Long cycles of monetary expansion tend to be followed by higher interest rates. Think of the US monetary expansion of 1930-1960 and the surge in US rates from 1960 to mid-1980s. The monetary expansion from 2010 has been unprecedented in scale in modern US economic history. There will be consequences. Not least, all that borrowing by the US government will crowd out borrowing elsewhere, pushing up rates. All that monetary expansion will turn inflationary eventually, pushing up rates.

Can the Fed buy unlimited amounts of debt? In theory, it can. It can just create more “paper” money (a liability) to pay off reserves (another liability), if they are ever called upon to “pay up” by banks. However, in the process, its balance sheet gets so huge relative to its capital that the financial stability of the system comes into question.

As much as the USD 250 billion Fed Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility sounds, it is worth remembering that by end-1Q20, the total amount of corporate debt in the US was USD 10.5 trillion, and rising rapidly.