Macro Developments and Factor Performance

The experience for those allocated to Chinese stocks in the first half of 2024 will be familiar to many value investors: belief in the promise that China’s economic future will be better than its recent past, but frustration that the catalysts for unlocking that value have been so elusive. The fact that stocks in China’s mainland CSI 300 Index rallied over 3% in Q1, only to give back nearly one-third of those gains by the end of June served as a reminder of multiple false starts witnessed since a pandemic-era shock and property market deleveraging sent China’s economy into the doldrums.

Of course, everything is relative. The growth ‘doldrums’ for China, used to seeing its economy expand at a remarkable pace over the last two decades, represents its expected growth slipping to “around 5%”—Beijing’s official target over the last couple years—after slumping to 3% year-over-year in 2022 amidst large-scale lockdowns (see Figure 1, below).

In part, investors’ hopes that China might be on a path to recovery at the end of Q1 stemmed from April’s report that GDP in the first three months of the year expanded by 5.3% year-over-year, well above analysts’ 4.6% consensus forecast for the quarter. But then there was news in mid-July that Q2 growth had come in at a lower-than-expected 4.7%, pouring cold water on the optimists—though still putting policymakers within striking distance of their 5% full-year target.

Yet, is that target what investors want to see out of the world’s second-largest economy, once expected to surpass the US in size before the end of this decade? Definitely not. On the other hand—and again zooming out and looking through the lens of relative growth—even the current official target of approximately 5% is well above the 2.3% average annual growth rate for US GDP in the decade prior to the pandemic (depicted in the chart above). It is also higher than growth achieved in South Korea and Taiwan, whose economies expanded at average rates of 3.5% and 3.7% respectively, over the same period. Investors would naturally be happiest with something like India’s growth over that span, averaging 7.3%; or China, itself, growing its economy by 7.7% per year before COVID came along.

While the second quarter’s GDP growth was surprising in terms of just how soft that headline growth rate was, the trends underlying that number were much more predictable. Manufacturing and export growth continue to be a bright spot for China, with domestic demand representing the very obvious weak link. That divergence was clear from a decomposition of Q2 GDP, but also in trade data for June, released around the same time. On the face of it, those trade figures seemed to offer a positive sign, with exports growing for the third month in a row, leaping 8.6%, higher than economists’ 8% consensus forecast and May’s 7.6% rise.

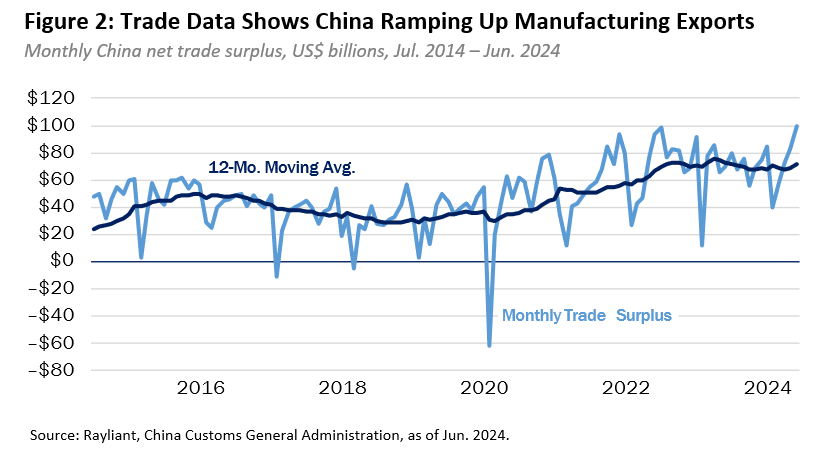

Strong export growth has certainly helped to offset China’s weak domestic economy, and much of the fiscal stimulus we have seen so far from Beijing has been to boost manufacturing, which is showing up in a flood of higher-value goods into foreign markets—things like electronics, EV and green energy tech. On the other hand, it is the very success of this drive to boost exports that has got some of China’s biggest trading partners, including the US and Europe, crying for trade protections. In fact, pundits believe part of the June jump in exports is the front-loading of orders to get ahead of expected tariffs. An even more apparent problem is visible in China’s net trade surplus—the difference between exports and imports—which totalled US$99 billion in the month of June alone, a record-high sum (see Figure 2, below).

Rising exports contributed, but another part of the equation is imports, which unexpectedly fell in June: an indication of how weak China’s domestic consumers are at the moment. With exports sensitive to trade frictions and potential weakening in the US economy, slumping imports highlight a real vulnerability for a recovery dependent on foreign demand. It is not that success in exports will not be part of the solution to China’s broader economic issues: we believe it definitely helps in the short run. However, in the longer term, we do imagine more fiscal stimulus is needed to successfully kickstart growth in domestic demand. In that sense, as we have mentioned before, some of the ‘bad news’ revealed for Q2 should induce greater policy support on the demand side in the second half, with Beijing’s full-year GDP growth target still very much within range, but base effects not as favourable as over the past six months.

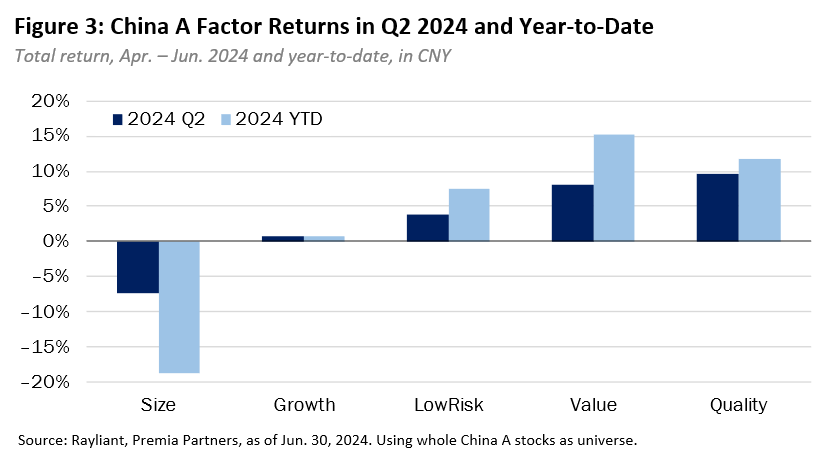

Needless to say, everything discussed so far relates to the beta of Chinese stocks. Factors tilting a portfolio toward stocks with more favourable characteristics present the potential for earning alpha in inefficient markets like China’s. In that respect, the second quarter looked much like the first, with factors like Quality, Value and Low Risk adding to their Q1 gains, Growth continuing its flatline performance, and Size making another very poor showing (see Figure 3, below).

In reconciling the Size factor’s sizeable drawdown last quarter, we cited mean reversion after a stellar 2023, along with National Team buying concentrated in larger-cap stocks as driving a wedge between big and small firms’ performance in the first quarter. While those dynamics were still undoubtedly at play in Q2, small caps were not helped by an April decree by China’s State Council threatening delisting for stocks falling short, for example, on revenues and net income. Witnessing a small-cap selloff in the wake of the rules change, authorities were quick to clarify that the new policies were meant to root out “zombie” firms and “bad actors”, not punish small firms—messaging that apparently landed with investors, as the vast majority of the Size factor’s underperformance in Q2 came in April. Early July brought potentially better news for investors with a small-cap tilt, as the National Team was seen putting money to work in small-cap ETFs.

Index Performance and Outlook

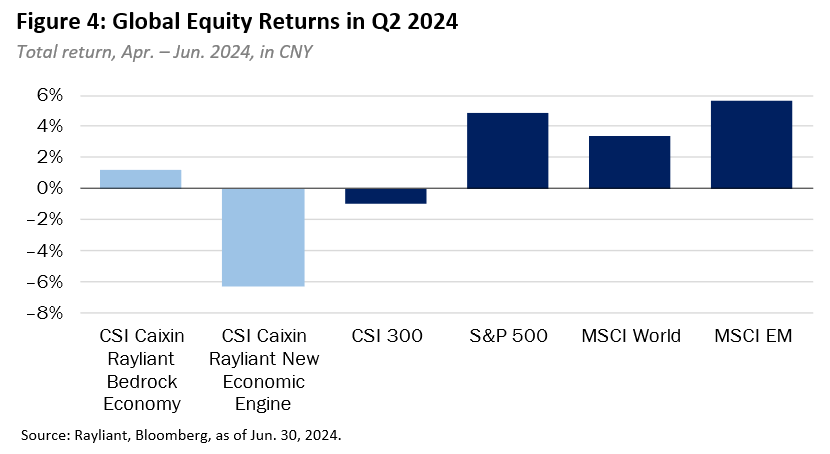

With macro developments in the second quarter leading investors to question China’s economic growth trajectory in the quarters ahead, it is not surprising that the country’s equity market, represented by the CSI 300 Index, lagged the broader emerging markets, returning -1.0% (CNY) versus a 5.7% return for the MSCI EM Index (see Figure 4, below). That emerging markets generally did well in Q2 was also to be expected, as developing economies tend to be particularly sensitive to news on US interest rates, and the second quarter brought plenty of that, as prices seemed to resume a disinflationary trend and the US economy appeared to be cooling after a first-quarter scare on the inflation front.

Rising confidence that the Fed might stick a soft landing, combined with ongoing investor enthusiasm toward stocks with exposure to the AI theme, led the S&P 500 to a 4.9% gain in Q2, once again dominated by growth shares with a handful of stocks strongly outperforming the broad market. Developed markets outside the US were modestly negative over the last three months, weighing down the return on the MSCI World Index, which was nonetheless up 3.4% for the quarter.

The CSI Caixin Rayliant China A indices picked up in Q2 where they left off at the end of March, delivering mixed performance in line with their intended factor tilts. The CSI Caixin Rayliant New Economic Engine Index (tracked by Premia’s 3173 HK/9173 HK ETFs) returned -6.3% for quarter, while the CSI Caixin Rayliant Bedrock Economy Index (tracked by Premia’s 2803 HK/9803 HK ETFs) managed to buck the broader market’s loss and post a positive return of 1.2%.

Given the underperformance of small caps in the second quarter, the New Economy strategy’s Size exposure was once again the most significant detractor at the factor level, with little help from its Growth tilt to compensate. At the sector level, an overweight to Health Care and underweight to Financials, along with weak stock selection among Industrials and IT stocks contributed to the drag on New Economy performance, offset somewhat by a meaningful underweight to Consumer Staples, the second-worst performing sector in the benchmark during Q2.

The Bedrock strategy was likewise underweight Staples, which helped, alongside markedly better performance for Quality, Value, and Low Risk factors.

Going forward, as the foregoing commentary should make clear, we see big value in onshore Chinese stocks, though it is increasingly evident that manufacturing strength alone will not be enough to propel growth to policymakers’ 5% target without some help on the part of domestic consumers. That once again puts a ‘bad news is good news’ dynamic in play, where the chance of demand-side stimulus increases as more macro data show exports and domestic consumption moving in different directions.

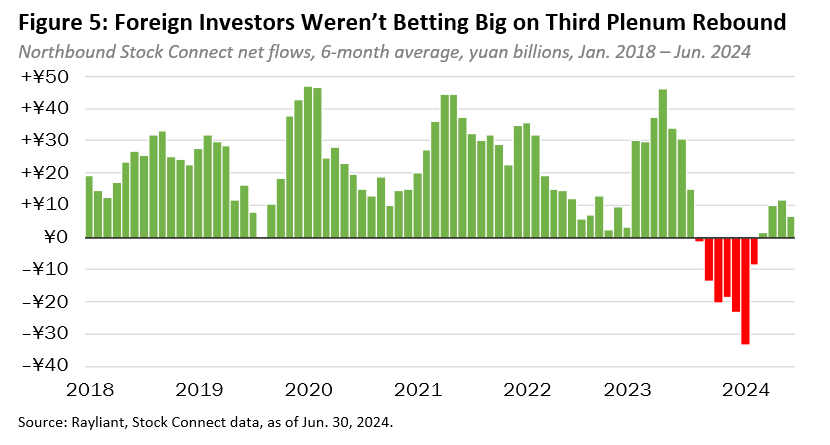

In the meantime, factor investors with more of a bargain-hunting approach to buying high-quality companies and growth at a reasonable price will find ample opportunity to allocate, while passive money waits on the sidelines. That tentativeness was on display in Q2, as many foreign investors—Rayliant’s team included—heavily discounted the possibility that July’s installment of the delayed once-every-five-years Third Plenum meeting of top party officials might yield any bombshell announcements of stimulus. After rare net outflows from Chinese stocks on the part of foreign investors in the second half of 2023, foreign capital has only been slowly coming back in over the last few months on bets of a market-moving outcome to the Central Committee’s July assembly.

On the flipside, the National Team—a source of frustration to those betting on small-cap stocks, as we discussed above—has been reportedly stepping in this year to give equities a lift, with Bloomberg Intelligence estimating over US$50 billion in flows from the National Team so far this year buttressing onshore equity index ETFs. The fact that we have not seen bazooka-style stimulus or some other major change in the party’s direction does not stop us from drawing more nuanced conclusions from those meetings that could be of use to investors in Chinese stocks. First and foremost, Beijing reiterated a message we have been delivering time and again: that policymakers are laser focused on “high quality” growth as the nation’s number-one priority over the next half decade and beyond.

For investors, that means a policy tailwind for companies in China’s high value manufacturing space, charged with furthering the country’s massive lead in green energy materials and technology, as well as making the nation technologically self-sufficient in areas like semiconductors, where China has a strategic interest in fostering homegrown success. Along those lines, with so much drama around the upcoming US Presidential election in November, it is clear to us that regardless of who wins, America’s policy of trying to “contain” China’s technological advance will continue to catalyze growth of select industries and companies in the areas just mentioned. We also see an opportunity in bedrock sectors like Industrials and Consumer Discretionary, where many stocks are trading at extreme discounts, and where we believe a revaluation will be strongly felt when China’s economy does turn the corner and sentiment improves especially given currently the very light investor positioning. When that happens, of course, is anyone’s guess, though we continue to believe the present gloom among China traders—both foreign and domestic—represents a great window of opportunities for contrarian investors to bargain hunt and diversify into high-quality Chinese stocks trading at valuation way below historical averages.

*****************************************************************************************************

Dr. Phillip Wool is the Global Head of Research of Rayliant Global Advisors. Phillip conducts research in support of Rayliant’s products, with a focus on quantitative approaches to asset allocation and return predictability within asset classes, as well as the design of equity strategies tailored to emerging markets, including Chinese A shares. Prior to joining Rayliant, Phillip was an assistant professor of Finance at the State University of New York in Buffalo, where he pursued research on quantitative trading strategies and investor behaviour, and taught investment management. Before that, he worked as a research analyst covering alternative investments for Hammond Associates, an institutional fund consultant. Phillip received a BA in economics and a BSBA in finance and accounting from Washington University in St. Louis, and earned his Ph.D. in finance from UCLA, where his research focused on the portfolio holdings and trading activity of mutual fund managers and activist investors. Premia CSI Caixin China New Economy ETF and Premia CSI Caixin China Bedrock Economy ETF track the CSI Caixin Rayliant New Economic Engine Index and CSI Caixin Rayliant Bedrock Economy Index respectively.